Joelle Biele

by Ann Fisher-Wirth

Wings Press

2009

$16.00 (pa)

Mapmaking

“We have not solved the problem of love, / have we?” asks Ann Fisher-Wirth in her book-length poem, Carta Marina. Fisher-Wirth, a professor of English and Environmental Studies at the University of Mississippi, spent ten months as a Fulbright professor at Sweden’s Uppsala University where she became fascinated with the literal Carta Marina, a rare fifteenth-century map of Scandinavia housed in the university library, which became the framework for her Carta Marina, a map of the ties that hold people together and pull them apart. A book of unflinching honesty, Carta Marina is an absorbing meditation on love and grief.

Organized chronologically over the course of the 2002-2003 school-year, Carta Marina reads like a novella. The book centers on the reappearance of a lost love. After decades of silence, the man, now a doctor living in Paris, contacts the speaker by email. They begin corresponding, and soon memories of the speaker’s failed pregnancy begin to surface. In two moving, back-to-back poems, “October 28” and “October 30,” she recalls what happened after the first signs of miscarriage. Speaking of herself as “the girl” and the man, who remains nameless throughout the book, as “the boy,” she says:

With that blood,

oh her warm

body soft as a moth’s wings

starts down its long

road toward November,

toward the forceps,

the stillbirth, the hospital bed—

The line-breaks emphasize the impact of the loss, slowing it down by breaking after the adjectives, and leave the story hanging on the dash. What follows this organic lyric is a prose poem that again pictures the pair asleep in bed, bluntly reporting “that moment before the moment” when the boy did not fear “what he will fear for 37 years, and never spoke of to a soul: that he murdered her child by fucking her.” With the story in two strikingly different forms and additional details emerging later in the book, sometimes revising preceding lines and previous poems, the speaker’s struggle with this loss is clear.

One of Carta Marina’s most appealing characteristics is its candor. Fisher-Wirth does not shy away from showing her speaker’s conflicting emotions. Contemplating her entrance into old age and learning of her declining health, she is aware that reconnecting with the man could hurt her husband. In one of Carta Marina’s standout poems, “April 10,” the speaker is torn between her long, satisfying marriage and the memory of transfiguring love. On that snowbound day, she writes:

My leg across Peter’s belly,

I said, “I love you both,” and he smiled,

held me. He said “I love what is real.

Her husband’s understanding of her need is both tender and profound. By “April 20,” the speaker is preparing to let the man and child go.

As counterpoints to the speaker’s story, Fisher-Wirth includes poems and images that develop the themes of lost youth and love. As she says in “November 2,” “You get to the point where everything becomes metaphor, / everything becomes signal.” One poem is about the murdered student activist Rachel Corrie and others refer to the deaths of former students and the 2003 invasion of Iraq. In “March 30” the speaker relays the story of witnessing a young woman giving up her child for adoption in the same hospital where she was recovering from giving birth. Using images of the wintery Swedish landscape to address an urgent sense of mortality, she also has some superb passages on the Gustavinium’s Anatomical Theater and its paintings of the human body to illustrate the many sides of the speaker’s psychological state.

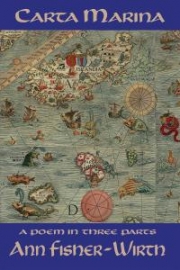

Throughout Carta Marina are poems about the map, which is reproduced in full in the book’s center. The map poems serve as points of reprieve from the rest of Carta Marina’s intensity. These poems attempt to visually recreate the map by playing with the margins and typography, so the reader can share the speaker’s fascination with cartographer Olaus Magnus’s images and stylized prose. Like Elizabeth Bishop, Fisher-Wirth sees a parallel between the poet’s work and the map-maker’s. Both are intent on accurately describing their worlds.

My only hesitation about the book is what feels like an over-determined beginning and an almost closed end, the problem of getting into and out of the story. The first poem neatly lays out the major themes, which was perhaps meant to serve as a key. The penultimate poem is a catalog of goodbyes, creating an artificial sense of closure. By announcing goodbye, writing it, as Bishop would say, but without her punning irony, the speaker draws what seems like unnecessary attention to a need that is already clear. The poems interfere with the book’s narrative suppleness, which Fisher-Wirth renders so beautifully throughout Carta Marina and in its last lines:

The split heart—

The heart still split—

All this human love and anguish—

Fisher-Wirth writes with great sensitivity and intelligence. She is a poet of terrific formal dexterity. As her images accumulate, she creates depth and contrast, variety and coherence. Fisher-Wirth tells her story with haunting power. She makes a map of many shades.