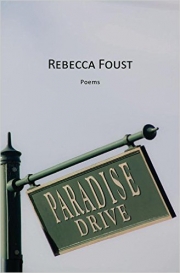

Lee Rossi

by Rebecca Foust

Press 53

2015

$14.95

Rebecca Foust’s new book, Paradise Drive, the winner of the 2015 Press 53 Award for Poetry, is a diary in verse, reminiscent in subject and technique to Vikram Seth’s Golden Gate. Drawing on Pilgrim’s Progress, John Bunyan’s allegory of trial and redemption, as well as the English sonnet’s tradition of spiritual encounter, Foust’s sonnet sequence dramatizes the protagonist’s journey toward greater self-awareness. In the beginning we see Foust’s alter-ego Pilgrim adrift in Marin County, California, where life is la dolce vita, a never-ending party. Unfortunately Pilgrim has been party to the party for too long; her life of privilege has become both Vanity Fair and Slough of Despair.

Yet much as this book recalls Bunyan’s Puritan epic, it is also something quite different. There is a joie de scrive in these sonnets, which is both counterpoint to its heroine’s quagmire as well as its objective correlative. How long have we been waiting for someone to rhyme deus (as in deus ex macchina) with Prius! Like the Windhover, Foust’s vocabulary soars and plummets. Her quite considerable accomplishment is to have written a book that is vivacious and filled with snark (even if much of the snarking is directed at Pilgrim herself) while almost never losing sight of an underlying seriousness.

Where we start is “Paradise” (Marin, of course), near the green jewel of a lake, surrounded by mule deer and the tufted bobcat, where all the treasures of an earthly Eden – “Peonies under palms, cactus next to the fat pout of pink hybrid tea” – co-exist, we can only guess how happily. We note, for instance, not just wild iris – an allusion perhaps to Louise Glück, high priestess of suburban distress – but also the “air barrel-aged in live oak and madrone,” shorthand, no doubt, for the high-living wine-soaked life style. In this idyllic setting the narrator warns us, “each day [is] bound to the last with dark thread.“

The title of the first section, “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell,” points us, of course, to Blake, and his awareness that the awful and the sublime fitfully co-exist in human life. Nor should we forget Mr. Blake’s mystical impulse. When we first “Meet Pilgrim,” she has everything – comfort, security, all the many pleasures of the senses – but wakes one morning “wanting – nothing – in the way of things. Wanting some not-thing not quite not-seen.” Already, as her name suggests, she is a “seeker, someone who leaves [her] home.”

But first she must retrace the steps that have brought her to this impasse. Unlike Christian, Bunyan’s hero, Pilgrim is not an Everyman, nor even an Everywoman, but one of the privileged few, and more than that, a radical with a bad conscience. The word Pilgrim, she tells us, “constellates a whole world: girl, glim, imp, grip, grim . . . holds – good and bad – what I am, featured in its radicle form.” For a while now, she’s been out of tune with the Marin party line. In fact, she spends most of her time at parties hiding out in the bathroom, reading the Times or WSJ or, on one desperate occasion, Your Bird Dog Today. Eventually she brings her own stash, Pound’s The Cantos, a real heavyweight.

But there’s no escaping her feelings of malaise, and so Pilgrim embarks on what some might call a “fearless moral inventory,” which, in the preferred vernacular of this book (Christian and Medieval) we should rather label an “examination of conscience,” as she interrogates both herself and her social set for violations of the 7 Deadly Sins, an act both satire but also a mea culpa for her own complicity.

The music is exhilarating, giddy, full of assonance and assurance, laced with end- and internal rhyme – full, feminine, and slant-. Here, for instance, is Gluttony talking up her latest diet:

In my famine

landscape, each rag and bit of color

is carnival. From the dolor

of hours stung numb, a sermon

of grace is sung. But a tongue never tires

of honey left wild to steep in the comb.

There’s so much to enjoy here. In addition to the gracefully casual allusion to Yeats, we experience the almost Metaphysical balancing of tongue, organ of taste, and tongue, the organ of speech, of grace said over a meal and the grace of self-transcendence.

Pilgrim is nothing if not well read. Here, for instance, from “Hard to Entertain,” is another shout out, this time to Dylan Thomas:

It’s not easy, being a good hostess

to all Seven Sins en masse. . . .

The pride masquerading as mean.

The hunger always through-the-fuse-green.

The book is pockmarked with allusions. In the poem “Archimedes Lever” we see her using a titanium dental probe to pry a couple of marble tesserae from someone’s fancy bathroom floor. The floor, she tells us, is “the best bit of mosaic seen since she left Pompeii . . . [and] artfully fuses ancient with new. Think Aristophanes in the mouth of Camus and Sartre: old ideas, modern milieu” – a description of the book itself, a tesserae of ancient and modern snippets.

Yet while it is often playful, the book never shirks from a process of painful self-evaluation. “Indentured,” for instance, is a sonnet about having bad teeth, a trait she inherited from her father. Not only do we return to the past to witness her father’s dentures “boiling Polident blue in a cup,” but also to feel the shame of the family’s poverty: “floss got reused, rinsed, and pinned to the clothesline.” (14) Poverty, in fact, was “The Prime Mover,” the central fact of her childhood.

Wealth and security are one kind of answer to a squalid childhood, but not a wholly satisfying one, not for Pilgrim. Finally she declares, in the words of Rimbaud, “Je Est un Autre,” I is an Other, a characteristically ambivalent declaration, suggesting not just that she doesn’t fit into Marin society, but also that she fits in too well. Even she “wears too much bling.”

Spiritual progress, at least for Pilgrim, does not come easy, despite all her fancy reading. At the beginning of Section 2, “The Fire Is Failling,” we find her “You-Know-Where Again,” some beautifully appointed bathroom. But this time she seems somewhat chastened, perhaps by the struggle, perhaps by her lack of progress:

No one knows I’m here, Pilgrim’s first thought –

and in the end her best thought –

followed by the less pleasant doubt

that she’d be very much missed

Here the allusion (to Ginsberg) seems less playful than pointed; she sounds rueful, and just plain lonely. If Part 1 is a kind of Purgatory, Part 2 is an Inferno, the pain closer to the frantically glossy surface. “Troth” (rhymes with Sloth and something we plight when we marry) recounts the death of her dog. The tone slices from harsh and sarcastic to sorrowfully sincere:

Shaved like a whore,

stapled and stitched and IV-cathetered,

he lies on his side, his monitor beeping

But it is not just the dog she mourns – she’d heard that death sound, the dog’s “agonal breath,” before:

Pilgrim’s father died – twice – like this.

Eliot (both The Waste Land and Four Quartets) haunts the second section, memory and desire quickening in spasms. Throughout we hear their insistent staccato music: “Does the fire / care what phrase names its fierce thirst?” Similarly bleak in its vision of the past, “Point of View” wreaks a systematic deconstruction of the family romance:

I, you, he, she, it, we or they

did it to me, you, him, her, us, or them,

or had it done. And so continue to do.

Desperation is the theme, as the sonnet “Despair” – “Sloth’s BFF and Faith’s worst foe” – admirably demonstrates. In fact, Pilgrim is first cousin to John Berryman’s Henry, the jagged, oracular musician of the Dream Songs! Like Henry, “Pilgrim was S-A-D sad. . . . Same old plague. Superbug strain.”

Pilgrim can’t seem to stop adding to the Catalog of the Deadly Sins. Regarding “Ennui,” she asks, “And wasn’t that its own sin? / To have it all, and still be malign and vile, / a wart on the face of esprit de corps?” Notice all those lovely ‘l’s’ piling up, like a chain-reaction accident on the fogbound interstate? Nor can she quite say goodbye to the Classics; “Bourbon Elegy” plays with the music of another soul-sufferer, G.M. Hopkins, as she tells Bourbon (the drink, not the royal family) how much she misses it and its:

. . . everythingbeautifulblur

jagged pink smearof each cracked-windowpane

shade-undrawn dawn

This is certainly not Hopkins’ “dapple dawn-drawn falcon,” but rather the emptiness of his absence.

Throughout the 2nd section the narrative arc is downward, with Pilgrim sinking deeper and deeper into the Slough of Despond. “How Then Shall We Live?” asks the title of one sonnet. “Kill yourself in a way that leaves the least mess” is the answer.

But kill herself she cannot, and life, in the form of 9/11 and the birth of another child, interposes. The poems in book’s last section, “O Earth Return,” trace a tentative and gradually accelerating recovery from the nosedive of Parts 1 and 2. The memory of her mother, an emblem of almost heroic self-sacrifice, points the way to a less selfish, more satisfying, life. As she tells herself in “How to Live, Reprise,” all one can do is moderate one’s aspirations and needs and try to accept impermanence:

Admit when you’re wrong. Go on

for the kids, especially the kids

you have personally caused

to be brought into the world.

Prepare for death, the poems in the last section tell us, but be thankful, every day, for life.

Unlike Parts 1 & 2, this section has a more linear narrative. We see her, for instance, attending twelve-step meetings, and before long achieving a kind of conversion. Perhaps this section is too straightforward, too intent on convincing author and reader that real change has occurred. Some phrases and passages seem both histrionic and overly calculated. For instance, we see Pilgrim at a “Twelve-Step Meeting”:

She rises and waits while they dim the dim lights,

then pulls from her clutch the small, silver knife

she’ll wield to lay herself wholly open

from mouth to crotch: one thin red, honest line.

But in general the writing is still compelling. Life continues, the poet observes, despite the sufferer’s pain, and sometimes healing takes place. “Some things we believe cannot be redeemed,” she tells us in “Vernal,” but even in places which she thought irremediably damaged, as for example, her Appalachian home:

Limestone spalls

hewn from the mountain heal into soil.

. . . The woods keep

a hushed vigil, then rustle with life we can’t see;

small ponds well from the ground while we sleep.

As the last line suggests, all will be well, and all manner of thing will be well, if we let nature do its work.

Near the book’s end (in “If Not, Winter) spring comes again to her neighborhood. “How the night air smells . . . like frangipani,” she says. And on the Bay she sees:

Frail sculls

pulling diagonals on wide pewter water,

looking back while drawn into the future[,]

those “Frail sculls” emblematic not just of her backward-looking, forward-faring heroine, but of us all.

Lee Rossi’s latest collection of poetry is Wheelchair Samurai. His poems have appeared in The Atlanta Review, Poetry Northwest and The North American Review, as well as on Poetry Daily and Verse Daily. His interviews and reviews can be found on thepedestalmagazine.com and Poetry Flash. He lives in northern California.