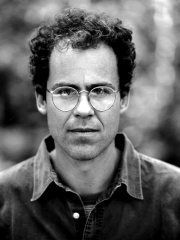

By Jacqueline McLean

Jeffrey Harrison’s Feeding the Fire is available from Sarabande Books (www.sarabandebooks.org). Harrison is the author of two previous collections, The Singing Underneath, selected by James Merrill for the National Poetry Series, and Signs of Arrival.

Jacqueline McLean: Titling a book of poems seems like a difficult enterprise. I want to ask you to talk about the significance of your title, Feeding the Fire. In presenting this question, I have a few thoughts in mind. First, there is your marvelous line from Kafka which prefaces the collection: “What one writes is merely the ashes of one’s experience.” This is a particularly apt line for poetry, in which we relive or try to recover something of the essence of what once was. Yet I see a contradiction here or at least an intriguing complication. In a poem like “White Spaces,” you recover (without bringing him back) a college professor who continues to compel you. The closing lines of the poem read:

Gone now, known too briefly and too long ago

for me to bring him back in a poem,

though I’d like to think that what he was

and what he gave me hover at the edges

of these lines, in the white spaces around them

…always asking what can be found in words

and what forever lies beyond them.

I love this closing couplet, for this is the stuff out of which a great conversation about poetry might be made. Is it right to assume that for you, in Feeding the Fire, the written word is both “merely the ashes of one’s experience” and “what forever lies beyond them”? I seem to see both of these energies at work, in fine tension, in the collection. Could you pick this question up and run with it?

Jeffrey Harrison: The Kafka quotation, along with the Bachelard and William Carlos Williams quotations it appears with, are an attempt to set up a metaphor for writing–and especially writing about memory, because this is sort of a memory-obsessed book. The idea is that we feed our experiences to the fire and watch them flame up in the act of writing, so in a sense these past experiences live again. Afterward, we are left with the ashes–which could be the poems on the page. Then, to extend the metaphor even beyond those three epigraphs, the reader breathes the ashes to life again in the act of reading–or so I hope.

The contradiction or tension that you see is definitely there, and it is there in most poetry about past experience or any kind of loss. The experience is gone, but in a sense you are bodying it forth again in language, so you end up sort of having it both ways. I cannot have my professor back in real life, but by writing about that loss I can, paradoxically, experience him again in language, and in the imagination–at least to some extent. The poem tries both to bring him back and to acknowledge that he can’t be brought back. This double-edged quality is, I think, an aspect of all elegies, and of many other poems besides, and it is part of the “redress” that Heaney writes about in “The Redress of Poetry.” I also like your word “recover.” We cannot bring back the dead, but writing the poem is a kind of recovery, in both senses of that word. But it’s only a partial recovery. There are hundreds of examples of this kind of poem, probably thousands, but a good one, just off the top of my head, is Larkin’s wonderful poem “The Explosion,” in which he envisions again the miners who have died in an explosion, and ends the poem not with their death but with “the eggs unbroken,” leaving us with the image of them before the disaster. The poem’s amazing power comes from that complicated relationship between loss and memory.

That final italicized couplet of “White Spaces” is also an acknowledgment of the limitations of language. Some things are, finally, “beyond words” in the sense that they can’t be expressed in words. And so we are bound to fail, over and over again. And yet we go on trying, and by trying perhaps find some sort of redemption in our failure. This poem, by the way, took me ten years to write and changed shape many times. I sent one of the drafts to someone who also knew Bert Leefmans, my professor–knew him, in fact, better than I did. Her letter, which was largely about how impossible it was to capture Bert in words, was so moving that I found myself wanting to use parts of it, and that’s how I came up with the idea for the inter-spliced couplets which appear in the poem’s final form.

McLean: I would like this interview to be useful for developing poets interested in putting together a first or second collection of poems. (And perhaps every poet is a developing poet.) As a teacher of poetry, I am drawn to your work because I think your organization offers a good deal from which other students and writers of poetry can learn. Would you discuss your method in organizing this book in three parts? Here, you might also talk about the relationship of the poems within a particular section as well as the relationship of the first poem in a section and the last. One point to focus on might be Section II, which opens with “The Burning Hat,” one of the poems that really moved me (a poem I shared with my creative writing students). This same section closes with “White Spaces.” How do these two poems frame Section II?

Harrison: I’ve assembled three book manuscripts now, and I’ve helped my friends do it, too, so it’s something I’ve thought about a lot. There are poets like Louise Gl�ck who write books as a whole, but many of us write one poem at a time so that when we are ready to put a manuscript together we have to find a way for the poems to work as a book. I usually end up on the floor, with the poems spread out all around me, making piles and looking for sequences. It’s like a huge game of solitaire that can take weeks or even months. There are so many ways that poems can be grouped–by subject, by theme, by style, etc. Are you going to put all the narrative poems together, or are you going to intersperse them with more lyric poems?–the way a rock band will alternate fast songs and slow songs. Now I’m mixing my metaphors. But going back to cards, it’s sort of like when you have one of those complicated hands in gin rummy where you don’t even know whether you’re going for runs of the same suit or groups of the same value (three-of-a-kind, etc.)–only there are more factors than that. In my last book, Signs of Arrival, I had to decide whether to group the travel poems together or intersperse them throughout the book. I tried it both ways (actually, several different ways with each of these approaches), then decided it worked best if most of them were in the middle section of the book. The first section could then become, loosely, a “before travel” section, containing poems about childhood, but also some other poems. The last section was harder to define, but it had “after travel” poems about starting a family, but also poems of the present moment. This simplified description makes it sound more coherent than it is, because not all the poems fit so neatly into the sections. You don’t want the sections to be boringly literal; you want a little “shake” in the thing. But there is definitely an over-arching structure, a trajectory.

In Feeding the Fire, I’m not sure I could even put into words what the three sections are doing. And it would take another long game of solitaire for me to remember everything I was thinking when I grouped them. But those groups are the result of a very long process of arrangement. One thing I didn’t want to do was to put the poems in a sequence that was too narrative in a linear way. If I’d wanted that, I would have started the whole book with “The Burning Hat,” because it is the earliest memory in the book. Instead, I tried to undermine chronology somewhat, and to intersperse other kinds of poems among the memory narratives, looking for other kinds of connections. After the first section, then, “The Burning Hat” becomes a kind of flashback, a new beginning. In some very general way, that section has something to do with losses, beginning with the seemingly trivial loss of that hat and including perhaps a loss of innocence, so it makes sense that it ends with a little sequence of elegies, culminating with “White Spaces.” But I saved one elegy for the last section, partly so that all of them wouldn’t be clumped together. That poem, “Arrangement,” is the penultimate poem in the book and comes right before “Car Radio.” That may seem like an odd juxtaposition, since they are very different, but the link there is that both are poems about driving.

Often one of the first things that happens when you look at your poems with the intention of arranging them into a manuscript is that one or two poems present themselves as good poems to begin the book with, or at least to begin a section with. One interesting fact is that those same poems often work well at the very end of the book or a section, so you try that too. But with this book, “Green Canoe” seemed a good introductory poem, even though it wasn’t written with that intention. After you have that first poem, you say, “Okay, what poem would work well next to that poem?” and you just keep going like that until you get somewhere or it dead ends. I put “Lure” after “The Green Canoe” for a couple of reasons. One is that it has the exact same setting (a lake in the Adirondacks) but it is a totally different kind of poem. On the continuum between lyric and narrative, “Green Canoe” is more lyrical, generated by its own sounds, by language, by voice, and by the metaphors it plays out. “Lure” is more narrative, and it is generated by memory, though sound and tone are still important, of course. “Lure” also introduces some different subject matter, the idea of sexual awakening, which comes up later in the book. By starting the collection with those two poems, I think I was able to give some idea of the variety of poems the reader would encounter in the book. The first section ends with “Rowing,” which on one level is very much like “Green Canoe”–a lyric poem about being in a boat on a lake, but by this time the theme of sexuality has been established and the whole poem becomes a metaphor for sex. Those two poems frame the section in the sense that they are similar, and yet we have arrived somewhere new.

McLean: I just watched, for the third time, Li-Young Lee’s reading and interview with the Lannan Foundation. In his interview, he talks about the lyric poem as an ideal vehicle for autobiography. His premise is as follows: If the self is always provisional and always in flux, then the poetic enterprise makes great sense for autobiography because poetry is about uncovering a self that might be different at each sitting.

There are many ‘selves’ in Feeding the Fire. Could you talk a little about your own thoughts on the relationship between lyric poetry and autobiography? Here, you might discuss “Car Radio,” the last poem in the collection.

Harrison: I’m intrigued by Li-Young Lee’s idea. I’ve always thought of narrative poetry as being the vehicle of autobiography, and lyric poetry as being almost a break from it. But I think I see what he means (though I haven’t seen or heard this interview). Lyric poetry would be autobiography in a less literal, less mimetic, and more indirect way than narrative poetry. It is not recounting former selves, the way memory narratives sometimes do. Instead, it becomes a portrait of the self at the moment of writing the poem. You might call it autobiography of the present moment, or autobiography in real time. Though I have never thought of it that way, I think I’m doing that kind of thing in the more lyric poems of this book–they can’t help but be, in a sense, the inner speech of the self. But I am also doing the other thing–the quasi-autobiographical narratives of memory. Not that the two modes are mutually exclusive. Some of the poems (“Family Dog” comes to mind) might be doing both at the same time–writing about memory in a way that encompasses the present moment.

“Car Radio” does try to capture, or at least address, that idea of the self in flux�and also perhaps the play between narrative and lyric, between memory and the present moment. As I said earlier, this is a memory-obsessed book, though there are lyric breaks from that obsession. “Car Radio” addresses this idea of recalling former selves, and you could say that the memory-narratives in the book are analogous to the switching of channels on the radio to get to different eras. In other words, I’ve been flipping channels all through the book. So this poem seems to look back on, and speak to, one of the major themes of the book, which is why it seemed like a good poem to end with. In the end, though, the poem wants to acknowledge that tendency to look into the past but leave it behind, opting for the present moment. So it ends on a more lyrical note.

McLean: How do you feel about revision? Is it a process you embrace or abhor? Who are your best critics?

Harrison: I revise a lot. It can be hard work, and sometimes you get that demoralizing feeling that you are never going to get it right, but the rewards far outweigh the frustrations. Revision can lead to new revelations as you delve deeper into the material. And even if you over-revise and end up going back to something like an earlier version, you have learned something in the process, and there is almost always something in the newer version that you want to take back to that earlier version. Usually, though, the poem gets better and you don’t go back. My philosophy is that it is almost never too late to improve a poem. Some of my poems go through so many revisions that I can’t even get a large paper clip around all the pages, and I have to move on to one of those black spring clips usually used for book-length manuscripts. Other poems don’t go through quite so many revisions, and a very few go through hardly any at all.

My best critics are Robert Cording, Baron Wormser, and Peter Schmitt, all good friends, and all good poets. They have totally different angles and almost never agree. I also periodically show my poems to other poet friends, including Karen Chase, Theodore Deppe, Jessica Greenbaum, and William Wenthe (I am probably forgetting someone), as well as to a few friends who aren’t poets, which can be very helpful because they think in other ways.

McLean: Would you talk a little about your writing habits?

Harrison: I’d say they’re kind of lax. I mean, I work very hard when I work, as the above answer would suggest, but I don’t have a routine, a special time to write, etc. I’m not sure poets should have a routine. Poems can come from anywhere at any time, but sometimes they’re just not coming, and although I don’t enjoy those fallow periods, I don’t think you can force poems to come. I think some poets write too much, or maybe they just publish too much. They work like coal miners, and their books come out in such quick succession that no one could possibly want the new one yet.

Let’s see. I like to have my desk up against a window so I can daydream. (I imagine novelists having their desks shoved up against a wall.) We have moved a lot, but that is one thing that has stayed the same. Right now, my “office” is a tiny alcove, a dormer window off the upstairs hall, but the desk fits right in there. My computer is somewhere else. I don’t write on a computer, but sometimes I tinker with a poem on it. I generally use the computer as a word-processor (which is a very weird term, like a cooking appliance).

McLean: Please talk a little bit about the creation of “Not Written on Birch Bark.” Do you see this poem as a companion piece or a poem in dialogue with other poems that foreground beauty, writing and imagination, and their relation to “a strip of birch bark/whose native blankness/seemed to ask for words/but left nothing to say.” Here, you might also discuss “Not Written on Birch Bark” in relation to other poems in the collection and in relation to all that your title evokes.

Harrison: It’s really a poem in dialogue with some of my earlier work. I used to write a lot of what would have to be called, for better or worse, nature poems. My first book is full of them, there are some in my second, and there are a few in Feeding the Fire. So it’s not as if I’ve totally stopped writing them, but there are fewer of them, and perhaps now they are a little different. At first glance, “Not Written on Birch Bark” seems to be a nature poem, and perhaps it is, but it is also a poem about the limitations of nature poetry. My earliest nature poems were written with a kind of innocence, as if there were no separation between nature and the written word–as if, in other words, the poems were written right onto nature itself, onto birch bark. While in some ways that directness may be refreshing, it leaves a lot out. This poem, for one thing, acknowledges the act of writing. But also, at the end, it addresses the, well, dead end of some nature poetry: nature is sufficient unto itself, and in some sense there is nothing you can say about it after you’ve named it. Of course naming things can be an essential act. But usually we try to do more: we make connections, spin metaphors, bend nature to our ends. This poem does that, too, since it seems almost as if nature has grabbed the paper from my hand and then planted the strip of birch bark in the path intentionally. But it ends on a note that tries to pare things down to what they really are and to acknowledge that nature really doesn’t have anything to do with us. The poem “Arrangement” wrestles with the same issue: our need to interpret nature as if it had some bearing on our lives, when in reality it doesn’t. And yet we do it anyway–it’s part of being human and definitely part of being a poet. “Arrangement” tries to look to nature for solace after a death while at the same time acknowledging that that solace is a human projection.

McLean: The form in which you wrote “Salt” is unique in the collection. It is a form most appropriate to the subject. Please say a little about the form and the subject of “Salt.” Did you write this poem in slanting three line stanzas from the get go? Or did the form come with the evolution of the poem?

Harrison: We moved over the summer, and I would have to dig through a lot of boxes in the garage to find the versions of that poem that would answer the question of exactly when that form asserted itself. But my recollection is that it happened fairly early and fairly naturally–it was intuition, not a conscious decision. And while William Carlos Williams did come to mind as someone who had used that form (also Stephen Dunn), I did not go back and make a rigorous study of the variable foot and the triadic stanza. The poem did go through a number of versions, and I remember that the first version arrived somewhere that was entirely unsuccessful. But then I worked my way through it again and arrived somewhere else. The poem always began with the kosher salt I grew up with and went on from there, but I had no idea where I was going. Somehow, perhaps, that open form allowed me to move easily from one subject to another, from the salt to my immersion in things Jewish at Columbia, and then, well. . . it was a total surprise to me when the poem then turned into a love poem and played itself out that way. There is no more satisfying feeling in writing poetry than when a poem arrives somewhere you didn’t expect it to.

McLean: “Golden Retriever” is a terrific, visceral poem. It’s part of Section II, and it is part of a remarkable series of poems. Can you talk about the relationship between “Golden Retriever,” “Another Story,” “Masturbation,” and “Smoke Follows Beauty”? How do these poems enter into conversation with one another?

Harrison: “Golden Retriever” was a weird poem for me, and one that felt good to write. It is much more oblique than many of my poems. Like “Not Written on Birch Bark,” it is a poem in dialogue with some of my earlier work in the sense that it speaks against a poetry of pastoral nostalgia. (I’m not sure I’m being fair to my earlier work, but what the hell.) I was thinking of the retrieval of memories and the tendency to light past events in a golden glow. So in a sense the dog is me, which is perhaps why I can speak harshly to it at the end of the poem. This poem felt very different to me as I was writing it, and that was exciting. I was on a different wavelength–the wavelength of an extended metaphor and a strong voice that felt new to me–and I just rode it out, profanity and all. The ending seems to call for darker memories, so “Another Story” seemed like a good poem to follow it with. It’s a different type of poem–more direct, more narrative (with the pun on “story”)–but hopefully it has some of the intensity of “Golden Retriever” in its attempt to capture adolescence. And then “Masturbation” seemed to follow naturally from that. It’s another extended metaphor (which almost sounds like an off-color joke, with that title), but only the title establishes the metaphor. Without it, the poem would be almost straight memory. So in mode or genre it’s something like a combination of the two preceding poems. “Smoke Follows Beauty” seems a little more innocent to begin with, but by the end the smoke seems creepy in a sexual or “deathy” kind of way. It’s a strange knot of poems, perhaps having something to do with a loss of innocence.

McLean: If you could share this collection with any poet, living or dead, writing in any language, with whom would you share Feeding the Fire and why?

Harrison: Wow, what a great idea!–being able to give your book to dead people. Can you also arrange for them to tell me what they think? You’re crazy if you think I’m going to limit myself to just one.

I’d start with Charles Baudelaire, because he was really my first revelation, when I read him in high school French class. Then Elizabeth Bishop, because she was my second major revelation (in college). James Merrill because he picked my first book for a contest and we became friends, and I’d like him to see what I’m doing now. William Matthews would be cool (I didn’t know him). Definitely Keats. Maybe Rilke, though he’s not going to like “Rilke’s Fear of Dogs.” I’m sure I’m forgetting somebody, but I doubt they care. And maybe I’ll leave the living alone, though it would be nice if it somehow fell into the hands of Seamus Heaney, but I don’t think he needs one more slim volume from another younger admirer.

McLean: Do you share your poems with your children? How do their responses shape the evolution of your work? What do you think a poet can learn from children? (Take this question any way you want to go.)

Harrison: At nine and eight, my kids don’t yet play a big role in my writing, except once in a while as subject matter. I’ve shown them a few poems from my first book, one about an otter, one about seals, etc.–poems which, in hindsight, seem almost to have been written for children. I don’t think they’re ready for my more recent work. On the other hand, I do think we can learn from children. When my kids were younger, they used to say things that sounded like poetry. Like: “Who makes the clouds move? Who put the bark on the trees?” Once they were looking out the window and one of them said, “The leaves on the ground are like a blanket,” and then the other one said, “The grass must be sleeping underneath,” and I thought that was a pretty good imitation of Robert Bly. They are definitely on a wavelength that we poets tune into sometimes.

McLean: What responsibilities do you feel the poet has to the community in which he lives? On a local, national or even global context.

Harrison: Answers to that question run the risk of sounding portentous unless they come from poets who came of age in places like Eastern Europe or Northern Ireland. And yet I continue to believe that, even in our society that largely ignores it, poetry has its functions–though one of them might be to write the poems as honestly as one can without worrying about such things. Perhaps honesty is the primary responsibility–honesty about oneself and about what the world is like. But there are numerous other traditional functions that continue to apply to poetry, if not to every poem: to praise, to give pleasure, perhaps at times to frighten or discomfort, to make us see the world freshly, to make sense of life, to delve into emotional cruxes, to keep the imagination alive, to keep the language alive without letting it become self-indulgent. There is a passage in Auden’s The Dyer’s Hand about the function of poetry which still gives me goose bumps every time I read it. He lists all the different things that poetry can do– “delight, sadden, disturb, amuse, instruct”–and then says, “but there is only one thing that all poetry must do; it must praise all it can for being and for happening.” Amen.

McLean: How is your current work in continuity with the poems gathered in Feeding the Fire? How is it different?

Harrison: I’m not sure, it may be too early to tell. So far, there seem to be fewer memory poems, but that could always change: I’m not going to turn them away if they come knocking at my door. Judging from the way I’ve progressed up to this point, I seem to write some poems that are of-a-piece with what I’ve done before and others that move away from my previous work–like two opposing tendencies that don’t cancel each other out. I think that is how this book stands in relation to my earlier work: a few of the poems might fit without much difficulty into my previous books, but others wouldn’t at all, in terms of style or content. If someone had told me ten years ago that someday I would write a poem called “Masturbation,” I would have laughed in his face. I think I’ve been moving fairly slowly from innocence into experience. It took me three books to get to sex, for instance, but I always was a late bloomer. And the poems about sex (I am probably making too big a deal out of them, because there are only a handful) tend to be submerged in metaphor, and that too was something I hadn’t done very often. I believe in writing the poems that come naturally, and yet, at the same time, there is an innately self-critical aspect of my personality that makes me want to move on to other things. A poem like “Golden Retriever” comes totally from that restlessness. A dissatisfaction with one’s own work can be demoralizing if you take it too far, but it can also be productive, because it helps you move on. I think there’s always part of us that wants to be writing poems that are entirely different from the ones we are writing. Anyway, we’ll see what happens. A few of the poems are funnier than anything I’ve written before, I think.

*

Jefferey Harrison’s third book of poems, Feeding the Fire, will be published by Sarabande Books in November, 2001. He recently finished up a three-year term as the Roger Murray Writer-in Residence at Phillips Academy, Andover, to spend a year on a Guggenheim Fellowship. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The Paris Review, Poetry, The Southern Review, Shenandoah, Ploughshares, and DoubleTake. (Photograph of Jeffrey Harrison by Richard Linke)

Jacqueline McLean teaches in the English Department at Texas Tech University, where she is also on the faculty of Women’s Studies and the Honors College. She writes and publishes poetry, fiction, biography, and critical essays.

Jeffrey Harrison is the author of three books of poetry: The Singing Underneath (E.P. Dutton, 1988), selected by James Merrill for the National Poetry Series, Signs of Arrival (Copper Beech, 1996) and Feeding the Fire (Sarabande, 2001). He has received a Guggenheim and NEA fellowship, as well as a Pushcart Prize, the Amy Lowell Traveling Poetry Scholarship and the Lavan Younger Poets Award from the Academy of American Poets. Visit www.smartishpace.com to read an interview with Mr. Harrison. (2002)