Beth Feagan

by Alex Grant

Wind Publications

2012

$15.00

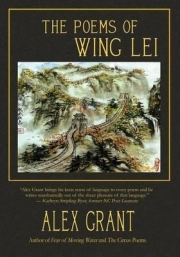

In a recent reading Alex Grant gave at Longwood, he said that during the writing of The Poems of Wing Lei, he became Wing Lei. This latest volume of Grant’s is about the life and poetry of ninth century Chinese poet Wing Lei, who lost his beloved wife, Nagini, in a flood. After her death, Wing Lei left his government position and took vows at a monastery, where he lived for seven years before traveling, writing poetry, and living on the charity of strangers. Grant’s voice captures the timeless quality of Chinese poetry, lyrical and rich, precise and evocative.

The opening poem, “Buddha Dream,” speaks to the attempt of the book as a whole to name the unnamable: “Also the white evening, pulling at something you are almost unable to name.” This impulse to capture the elusive and express it in poetry is echoed later in the volume in “Twilight”: “. . . row out to catch the reflection / of the moon in the water, unmade music ringing in their ears / like half-remembered songs hummed by children in the night.” So much of our experience is “half-remembered” and Grant gives the gift of individual moments, thoughtfully rendered. A single line rests at the bottom of one page, emphasizing the fullness of one moment, one bird: “This song, so late in the evening—this bird, holding on to the day, singing his heart out.” We are dropped down into this moment, not that one, hearing this song and no other.

In many ways, The Poems of Wing Lei is an act of recovery. Grant is recovering the experience of Wing Lei through his creative imagination, delivering to us a life of which many of us were unaware. Within the book is a trajectory of recovery too; Wing Lei must recover from the devastation of losing his beloved to the flood. The first poem contains the word “murder,” and while it’s in the context of “a murder of cawing crows,” it stands out as a sort of accusation, a hint of bitterness. Wing Lei knows “this may all be a dream,” but it doesn’t alleviate his suffering. In “Wine,” when he has had enough wine, he feels he has “small moments of realization—floating to the earth like petals.” He wants enlightenment, and sits patiently waiting for it, but his suffering overwhelms him: “The Buddha sat for forty-nine days under the Bodhi tree, waiting / for enlightenment. Two hours under this Juniper and all I can think / of is Nagini. Thus is the second noble truth of the accumulation of suffering.” In “At The Doll Shop,” his longing is palpable: Wing Lei watches a man and his wife gazing at a china-doll, and he moves toward the sake-house, an observer but not a participant in the dance of love. He is bereft as he moves “past the lady and her man” and he seeks comfort in drink.

Yesterday, as my friend lay recovering from surgery to remove a cancerous tumor from her parathyroid gland, sweating, hot and suffering, I fanned her with my copy of The Poems of Wing Lei. Still bleary from the anesthesia, she asked, “What is that?” I told her the premise of the book, and she asked me to read some poems to her. So I continued to fan her with Mary Oliver’s Blue Iris while I read from The Poems of Wing Lei. I chose “Song,” with its beautiful assonance: “dust-motes floating,” “ragged red prayer-flags,” “his skin chapped by the thin wind,” “hissing stars disappearing below the horizon.” The humble priest hums “a song his father taught him” and the lyrical language of the poem suits the subject of a song handed down from one man to his son. My friend murmured, “That’s beautiful.” Next I read “The Tea House,” a poem full of careful attention to detail: “A sprig of cherry blossom lies in the center of a plain white plate, / two sliced red plums arranged around it—the chopsticks rest on a white / napkin, pristine and perfectly square . . . ” As I read to her about the attachments that “. . . we hold on [to] like drowning men to driftwood,” she closed her eyes and let the cup of ice chips fall from her hand. I finished reading the poem before I stooped to clean it up, and a young male nurse stood listening at the foot of her bed while I read these and other poems. There was something sacred about reading to a woman who could barely swallow from the intubation and the incision in her neck, but who kept whispering, “Please read one more.”

We recognize each other’s suffering. Sometimes words soothe us; sometimes we have wordless exchanges. At the end of “The Inn-Keeper’s Wife,” a woman “[s]even years widowed” and Wing Lei pause in the street after he bows to her, and “Without speaking, we exchange our condolences.” Grief recognizes its fellows. In “On Waking From a Dream,” Wing Lei dreams of his wife, and sees her even after he awakes and goes outside looking for her: “I see her there, her head thrown back—laughing / at some story—she looks at me, holds her hands / up and waves, dives in slow-motion into the river.” Wherever he looks, he sees Nagini.

At the end of “The Hanging Temple at Hengshan,” which Grant read aloud at the Longwood reading, Wing Lei is sitting on “the promontory” overlooking “the foothills spread below.” He thinks of his wife as he sits alone drinking wine, and when Grant read these final lines, I wept:

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . I pour another cup of wine and think

of my wife, of the boyhood games in my village, of the way

my grandmother’s hands shook when she touched my hair—

I gulp the wine, watch a pair of red eagles riding the updrafts.

The juxtaposition of the man sitting alone drinking while watching a pair of eagles is so powerfully moving. Wing Lei’s grief and longing leap off the page. In the penultimate poem, Wing Lei dreams he is the one drowning: “. . . and I was drowning by the shore, calling out / to these birds who heard nothing—their blue beating wings washing me back out to sea.” Yet for all his grief, Wing Lei endured, and translated his pain into poetry. Grant entitles the final poem “Nagini,” and the last lines speak to Wing Lei’s continuing devotion to the memory of his wife: “. . . Years later, facing / the universe on his straw bed, he recalled the girl in the pink kimono, who / smiled as she stepped from the ferry—Nagini—my heart stopped for you.” Grant’s poems provide a sort of temporary immortality, where song and longing sift through centuries, settling like gentle dust.

Beth Feagan wrote a memoir of her childhood as her MA thesis at Longwood University, and is pursuing an MFA in Children’s Literature at Hollins University. She teaches at Longwood. An active member of MLA, ChLA, ICFA, and the Southern Humanities Council, she has presented at each of these organizations’ conferences, and serves on the Executive Board of SHC. She lives in the country near Chase City, VA with her son.