Clare Banks

by A.E. Stallings

Triquarterly Books/Northwestern

2006

$14.95

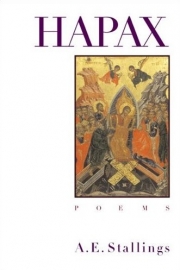

A. E. Stallings’ poems in Hapax, her second full-length collection, are striking in form and subject. Many pair contemporary formalism with allusions to Greek mythology. This intersection of form and subject is pervasive and important in that it echoes the collection’s thematic thread: most of the poems deal with the liminal, in particular, the threshold between innocence and experience.

This is most apparent in the several references to the myth of Persephone and Demeter. My favorite is in “First Love: A Quiz”:

The place he took me to:

a. was dark as my shut eyes

b. and where I ate bitter seed and became ripe

c. and from which my mother would never take me wholly

back, though she wept and walked the earth and made

the bearded ears of barley wither on their stalks and the

blasted flowers drop from their sepals

d. is called by some men hell and others love

e. all of the above

As in the myth of Persephone, Stallings seems particularly interested in subjects on the verge of knowledge, or those who have gone over its precipice. In “Amateur Iconography: Resurrection” we see Eve grieving the loss of the hand that held the apple. Though I doubt we are to believe Eve or Persephone regrets her consciousness.

Stallings’s concern with consciousness or a loss of innocence recurs throughout the volume, especially in her references to souls in Hades who seem to have acquired the greatest understanding. We see an interesting take on this in “Song for the Women Poets” where the subject is bound to both Hell and the living world:

Don’t look back. But no one heeds.

You glance down in the water,

The image drowning in the weeds

Could be your phantom daughter.

And part of you leaves Tartarus,

But part stays there to dwell—

You who are both Orpheus

And She he left in Hell.

Not all of the poems in Hapax employ form or allusions, but the best do. I’m not convinced that the use of form or allusions makes them more significant. It may be simpler than that. They may be more transparent, as if Stallings presents experience most clearly in contrast to the mythic and most precisely in form.

[reviewed June 2006]