John Poch

by Lisa Russ Spaar

Persea

2012

$15.95

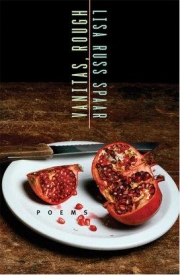

In Lisa Russ Spaar’s new book, though never mentioned by name, Persephone is the presiding genius. Persephone’s presence is felt severely, mostly in meditation of the Underworld or winter just outside its domain. In the first poem, “St. Protagonist,” we begin, “It’s bedtime. Tell me a story.” No children’s book here. Thrust into this acute irony of “bedtime”, we begin at the end. In these poems, we will encounter the poem beyond a story “improbable…but nonetheless believed,” the more ecstatic world that night affords us: sex, insomnia, death, and what Wallace Stevens calls the “mind of winter.” The cover image of the book is a still life featuring on a white plate, what else?—a pomegranate.

Due to the compact lines of the poems and an intense diction throughout, the words are vivid as the objects of avanitas, or a particular kind of still life (in some languages referred to more brutally as dead nature), plucked, arranged, set on a table awaiting a certain slant of light and a beloved to behold them. However, the careful reader does not feel this romantically. She experiences a beloved who, addressed throughout the collection, is missing in action, creating room for the impeccable silence in which each poem will be heard. The words are rich and difficult:boscage, parousia, horaltic, hibernalphilia, niveous, byssal, trencher, brumal, ordure, regnant, augend, corms…these words we encounter, and even if we know their meanings we want to look them up to find the etymological roots. This kind of linguistic and lyric intensity galvanizes the poems and is closely reminiscent of Hart Crane along with his intractable optimism in the face of our (post)Modern, crowded condition and solitary striving. What could become the ferocious striving of a poet like Sylvia Plath is transformed into a fierce abiding. Never turgid, Spaar delivers her choices via the context of beautiful syntax—a passion for the precision of the more arcane diction when it appears:

Injurious, this color of birth

debriding plexal trees—…

like a knife these evenings—promoted

despite the still-cheap bare impairmentof thickets, woods, the civet, fasting

garderobe at all margins. (“The Middle Ages, Bonus Track”)

or

If ever more ravened, junked, numb-sconced

I could not recall it, sopping in aftermathdusk’s blossom bock, ink-musk ale

at rusted window screen, the annual carnivala neon embolism blurring the horizon’s black seam (“After the Meeting, a Red Fox”)

And Spaar is aware of that syntax, one that interconnects not only lines and stanzas but phrasings between the other poems in the collection. The closing couplet of “St. Bronte” casts back to that protagonist in the first poem: “St. Hope. St. Story. Is syntax erotic? / If so, please. Please read. Here.” Throughout, the speaker pleads to know through the motifs of eros and death in what manner the body is united with (and severed from) the soul. For instance, in “St. Chardonnay”: “Two throats & each a sacred force.” One for drinking wine, and the other for breathing out poems—both, the passages of our vital spirits.

No poet should try to emulate Emily Dickinson, as idiosyncratic as she is. If my injunction is true, it has something to do with the fact that Dickinson wasn’t emulating anybody else. She was using a form of common hymn quatrain, but that’s about where the influence of other poets ends. I warn of Dickinson, yet the more direct influence on Spaar may emanate from our first lady of American poetry. Spaar does more successfully with Dickinson than any poet I can think of. The short phrases, the resonant abstractions, the sublime images, the slant and intense internal rhyme/alliteration, Death in the crosshairs, and the authority of mystery all work together in these poems, sometimes directly invoking Dickinson, herself. Emily, separated from the world in so many ways, might be a kind of Persephone. The refusal to explain, the composure in these poems, even the audacious imperatives show a strength of resolve rarely found or believed in our overcooked times. “What doesn’t love / restraint?” Spaar writes at the end of “Kismet,” one of her more erotic poems. That kind of restraint.

A deeply religious paradox infuses many of the poems. In a poem like “Watch,” we are given the “Interior of the letter ‘O,’” // tick of a starving dialect.”(56) This notion of time becomes plural in its second-to-second movement, killing us, but then comes Time, Singular, which was always coming to save us: “I know // these instants until you arrive / as my rivals. Defeat them with your coming.” This returns us to the title to understand that “Watch” is not only the phenomenal object that tells time but the noumenal action of watching for the Second Coming. We’ve come full circle.

It is important to notice that the last word in that first poem is “believed.” Faith plays an integral role for this poet. Not that poetry can replace religion, but that the religious is embedded within the poem’s humility. “Tell me…teach me,” the poet prays. She figures mortality is only one side of the coin: “The lonely bliss of going / where the body cannot follow. / Of knowing the foreign heap you are.” Again and again in this book, the speaker embraces the humility Auden suggested when he wrote: “If equal affection cannot be, / Let the more loving one be me.” Not only is it humility, but the verse proclaims an obstinate refusal to bow before death, to answer it face to face, or skull to skull: “Without exultation, we’re all dead.” Spaar doesn’t try to revive the dead roses in this collection; she cuts them back further, with a faith in what pruning will do. The action is a Kierkegaardian move toward repetition rather than some passive, pining recollection. Winter is not to be dreaded, but loved; hence the poem, “Hibernalphilia.” This love is not some Pollyana blissfully singing, Less is more. Rather, it is Persephone insisting that Less is.

There is no blame in these poems aimed at the departed lover or the invisible/absent god (we can’t tell if it’s death, divorce, abandonment, or mere departure), but there is a deep grief imagining itself to be reborn, to become praise: “Autumn to winter. Turn again. Don’t end.” Like any good book of poems, you cannot finish it. “Don’t end,” we say to this book. It doesn’t.