Eric Hoffman

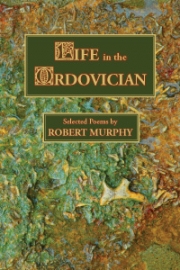

by Robert Murphy

Dos Madres Press

2007

14.95

In this excellent collection of poems, Robert Murphy’s language is elemental. The earth and his sense of the musicality of language are unparalleled: Murphy revels in language, and his reveling is a desire for revelation. Murphy handles our lexicon as a gardener handles seeds and plantings in a garden: placing words in perfect arrangement; and just as the gardener places certain plants in light or in shade, the poet places his words in arrangement of sound and sense. Murphy has dug deep into the dictionary for words most arcane and, having wiped away the grit of neglect, finds their radiance as music and meaning:

Mycelial synaptics, illuminate ganglia,

Increscent dendron’s mycorrhizals massed.

Excrescent swamp-rot sub-limen-arials.

Bog lanters. Slime candles. Thought truffles.

(“In His Image”)

Everywhere in Murphy’s poems are ruminations of man’s relationship to nature – how we as distinct beings fit into nature’s schema, and our many divergences with the natural order of growth and death. It is clear Murphy considers language the most natural and pure outgrowth of the human mind – not a shocking conclusion to be made by one who works so masterfully with words. The title poem is a meditation on “the role of the gardener,” one whose rightful place in the natural world seems assured:

Taking care to serve.

Almost as if the flower

Existed for the man in him alone

To bend to–

Praise requiring nothing of summer

Except to sometimes rain,

And the cold enough of winter

With a little faith to breathe in–

The air of its own accord

Carrying the sweet

Scent of flowers beyond a human use,

(“Life in the Ordovician”)

According to Murphy, the poems in this book proceed “in more or less reverse chronological order” and so we are presented with a kind of journey into the past. It is fascinating to see Murphy’s style change from the lush syntax and brave self-assuredness of the later poems to the more conservative, though no less skilled or self-assured, earlier ones.

In these quietly meditative poems, we are made audience to Murphy’s unobtrusive interactions with nature, with a fawn “light on dappled fur” who finds the speaker “of little interest” (“The Nap”), or an elegant, if sometimes prosaic, meditation on a blue jay (“ ‘Not Here,’ What the Blue Jay Tells Us Here”). Murphy finds the exceptional in the everday, which, by itself not necessarily a poetic strength, yet Murphy wrests from this everydayness the sublimity of true insight. Take, for instance, his humorous and deeply touching homage to Christopher Smart’s “Of Jeoffry, His Cat,” “Of Spot, His Little Cloth Dog”:

For he is named Spot, and has a black mark upon him.

For which he has barked fair warning, giving the Devil his due.

For this he is a little torn and tattered.

For this he has been broken and lost of a stitch or two.

For this he was unmade, to be made whole again.

There are poems here of quiet power and formal precision. Consider these lines from “For Every Thirst”:

From cupped palms,

my thirst an inverse praise

onto which that water falls.

Then overfills

where nothing holds

but overspills

to reach its common ground.

Note how the line ending with “water falls” falls over to the next line, “Then overfills,” which over fills the meaning of the previous line. Then, the pause forced by a line break provides a subtle shift in meaning, emptiness “where nothing holds” followed by a repetition of effect from the previous stanza, this time what overfilled now “overspills.” It is a pleasure to be made audience to such consummate skill and attention to the possibility of the poetic line. This says nothing of the equal attention to sound, the alliteration of the “r”-heavy “thirst an inverse praise” and the “w”-drunk line that follows, “which that water falls.” The “f” sound is carried over into “overfills,” so that the sound sense spills over with the meaning. In the next stanza, “holds” provides a nice off rhyme with “falls,” Followed by a full rhyme of “overfills” and “overspills.” The last line is a syncopated “to reach its common ground,” followed by the hard finality both in sound and sense, of “ground,” ending the poem. This subtlety and care of sight, sound and intellection is not an exception which proves the rule, however, for such attentiveness, is everywhere apparent in these altogether masterful and engaging poems.

Perhaps one of the poems themselves provides the best summation of Murphy’s poetry (one of his earliest, in fact, if Murphy’s reverse-chronological ordering of the poems is to be trusted):

All sleep

should begin like this: a sigh

that breaks open like the word violet

beneath spring rain. It is a color

you don’t have to look for, or need

to praise, but one that grows

out of its own accord.

(“When Talk Stopped”)

These poems grow out of their own accord, out of a need to please their own deep fascinations. Any reader with half an ear or eye would be in error not to recognize the talent here on display, the firm, yet self-assured hand of a gardener, tilling fertile earth.

Eric Hoffman’s prose have appeared in Jacket, Mental Contagion, Home Planet News, Galatea Resurrects, American Communist History and Isis. He’s edited a special feature on George Oppen which appeared in Big Bridge. His poetry has appeared in Cultural Society and The Argotist Online. He is the author of four collections of poetry, most recently Life At Braintree.