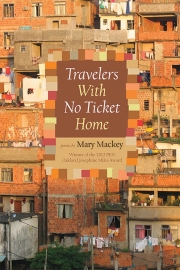

Zara Raab

by Mary Mackey

Marsh Hawk Press

2014

$14.25

In a sense, Travelers with No Ticket Home is a study in ethnobotany, the ways people and their cultures relate to the plants in their environment, the plants in this case being the lush and abundant flora, including hallucinogenic mushrooms, of the tropics, the people being two transplanted Americans fresh out of college. At its best, the book is an immersion in a phantasmagoria of landscapes whose surreal and liminal quality in these pages doubtless owes something to a narrator’s not being native to it, a Conrad describing the interior of Africa, a Kafka in Amerika. It’s a tropics of “beauty and mystery,” Mackey tells us in her “Acknowledgments,” she first fell in love with as an eighteen-year-old sophomore while auditing classes with Richard Evans Schultes, father of modern Ethnobotany at Harvard. Mackey spent a decade in Central America in the 1960s and 70s and later traveled extensively in Brazil, allowing her to interweave Portuguese words and phrases into her lines, and thus distil a steamy brew.

The poet’s fellow traveler and lover on this journey is himself a trip. “Chacruna Traz Luz,” he writes on the back of a photograph showing Brazilian tribesmen blowing LSD up his nostrils through hollow bones: “the head spirits are starting to speak / my body is dissolving.” Below that “in an almost indecipherable scrawl: [he writes,] get me out of here!” At carnival time on another occasion, he gets predictably carried away, dancing and chanting even when his feet become bloody “with the stigmata of […] martyrdom”. Another day, though warned of piranhas and stingrays lurking in the Amazon, he dives in, and with the same exuberance and arrogance, looks up from the depths (the poet tells us), and pities us “for not being able to breathe water” (“Black Water / Agua Preta“).

On occasion, the narrator of the poems joins her lover on his “trips.” Guided by a shaman, her consciousness expands until she is traveling “the plain of thorns” on hallucinogens, walking “to the aldeia dos mortos / the village of the dead / where the old grow young the young grow old / and women hunt jaguars under a snake of stars”. Characteristically, things quickly get out of hand:

you never mentioned the web that hangs between

the visible and invisible worlds

dancers who hold their eyes in their hands

the Boitata who glows in the dark

the Mapinguari who rips the tongues from cows

the Curupira who ear poachersyou didn’t warn me about os tunel de espinbos

the river of snakes the plain of thorns

Is Mackey here relating her own harrowing experiences? We don’t know. But the narrator of this account, writing in one poem of the two Hoosier great-aunts with “aprons full of chicken feed” who worry about a niece gone south of the border, never seems in fear of losing her “ticket home”—which is as good as having one. The poet and novelist Mackey—this much is public knowledge—does return to the States for advanced degrees and an academic career in the California State University system; she returns to middle class life, publishing seven books of poetry and 13 novels (some of them best-sellers) published by the likes of Penguin and Doubleday, and marriage to the environmental writer Angus Wright.

It is the poet’s companion who has no return fare to the cool rationality of North America. Mackey was lucky. Others from the 1960s era of experimentation and social change, what I call in one of my poems “the grand experiment,”—like her acid-dropping fellow-traveler—were not so lucky. One wonders what happened to the poet’s lover, the one who as Mackey memorably puts it, gave himself to the gods, but found it so very hard to take himself back. The legacy of this time is all around us, and never far below the surface of our best writings, but Mackey, at least in this book, has other business that the fates of the casualties of these culture wars.

Travelers, from a certain angle, is a love poem, and the poet’s wild, danger-seeking young lover is central to the book, but in “Fado of Two Lovers”, the affair begins to fray:

we came here as gods walking on broken glass

trailing auras of firenow we lie back to back

eyes shut fits clenched

wondering which of us will betray the other first

The relationship has its death throes in “Where I Left You” (“slumped up against a wall / sullen with a grief you refused to share”). There are, of course, parallels in literary history: The poet Elizabeth Bishop refers to it as a “disaster” in her famous sonnet about the end of her relationship of many years with her lover (a woman, as it happens) in Rio. I, for one, missed the lover in Mackey’s Travelers, and wished the narrator had returned at some point to the fate of this man who “gave [himself] to the gods.”

The narrator elaborates a landscape as magical as the rain in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Hundred Years of Solitude in lyric after lyric on the stupendous—from hurricanes to volcanic eruptions—to the simple—the “ghost corals” of a glittering reef, the scent of jacaranda, bundles of piassava, children hunting Easter eggs in an abandoned meth factory. Mackey shifts from the erotic and psychotropic to ecologic, expressed by a mythological goddess, Solange, spokeswoman for the indigenous Xingu River peoples who would be left without water, fish or livelihoods if a dam were built there. Here’s the zesty Solange:

when the colonels and their jaguncos [i.e., hitmen] come to kill her

she greets them by pulling up her skirt

which of you fat men with big guns and small pistolas

is brave enough to enter the door that leads nowhere she cries

which of you wants to die with the taste of cashews on his tongue?after they run away she sleeps for forty days

when she wakes she tells us to place another row

of small black seeds on her tongue calls them

the bitter stones that pave the path to Paradise

Solange also appears as the painted tiger stalking them by day; she is everything “we have destroyed [. . .]” Though Mackey does not directly address American corporation’s culpability, her text establishes a tension between the tropical landscape and the narrator’s more northern temperament, embodied in poems on her longing for snow and her wariness and fear in a climate that could quickly turn deadly: “[T]here are so many ways to die here,” she writes: from the river piranha to “that log lodged in the mud behind you / [. . .] an alligator with teeth like a cross-cut saw.”

Uneasy in the presence of unconquered and unconquerable nature, Mackey stitches past and present into a surreal tapestry, with the conquistadors’ violence mingling in the experiences of the two American Yankees: “we are fools and scoundrels / saints and sadists // we are two lovers in an apartment [. . . ] // we are the Portuguese coming into Guanabara Bay / waving at the beautiful naked people on the beach / who are waiting to eat us”. The narrator ponders the conquistador who” came to this place to conquer it”—

but how do you conquer mud and water

birds so bright they burn your eyes

women who can walk through trees.

Weather and climate become metaphors for culture and behavior: The cooler the clime, the more collected the inhabitants. Given the extremes of life in the tropics, life in the States is a vivid absence represented in her mind by “the flight of white owls [. . . ] / the hiss of our skates moving down creeks / over schools of fish frozen beneath us”. The poet returns to this longing for home in poems like “Os Perdidos / The Lost Ones.”

we long for snow imagine

inconceivable things mittens

the ache of frost

When, in the book’s final sections, the narrator steps outside the landscape, peering in from a distance, some of the magic dissolves as the text moves away from the sensuous to more abstract material.

The book’s strongest poems, to my mind, are those whose Fellini-esque exuberance roots them in the surreal, fantastic landscapes and people of the tropics. It’s as if the very presence of the Portuguese language in the poems frees the poet to be more sensual, more present in the moment.

over the sea the frigate birds hang motionless

parados congeladas

stopped in mid-flight like a flock of ethereal scissors

Travelers with No Ticket Home offers a vantage on the bright plumage of a strange world. Mackey’s material sings, and she has had the genius to see and shape into art her travels south of the border.

Zara Raab’s books are Fracas & Asylum and Swimming the Eel, and two chapbooks, The Book of Gretel and Rumpelstiltskin, or What’s in a Name? a finalist for the Dana Award. Her poems appear in River Styx, Crab Orchard Review, West Branch, and elsewhere. She lives in western Massachusetts.