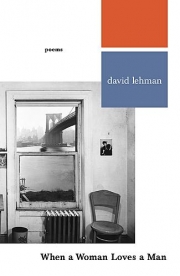

Jeannine Hall Gailey

by David Lehman

Scribner

2005

$17.00

When a Woman Loves a Man, Lehman’s best book of the last ten years, will shock few regular followers of his work. After all, we don’t read Lehman for his grand poetic ambitions, or his electrifying experiments in style, although this collection showcases Lehman’s deft hand with a sestina and an abecedarian. We read David Lehman for a particular kind of poem: humorous, at once upbeat and wistful, with a certain in-the-know, New York School-reminiscent cheekiness. This book manages to say something meaningful about love, pain, and prejudice, all in Lehman’s inimitable, whispering-something-amusing-into-your-ear voice.

The title of this book, taken from a song originally written and recorded by Billie Holliday (beloved of New York School poet Frank O’Hara and immortalized in “The Day Lady Died,”) tips us off that Lehman is referencing the New York School poets, about whom he wrote The Last Avant Garde. These poets, in an act of rebellion against poetry about statues, ancient mythology and history, and other “classical” objects, included references to real people, pop culture artifacts, and a world outside of the poet and his poem.

The book is organized into four sections: the first and second wittily examine relationships and philosophies, the third concentrates on poetry, and the last section consists of the somewhat expected, but nonetheless rather touching, post-9-11 New York-oriented pieces, as well as thoughtful pieces on other political topics. Individual poems from this collection were written and published as far back as 1998, so it is not, as were his previous two books, a snapshot of “a year in the life of Lehman.” In some ways this collection is more attentively organized, less random in feeling than either The Daily Mirror or The Evening Sun. In those two books, there was sometimes a feeling of too many “incidental” poems; in the worst cases, you could feel the effort of the poet going through his “daily poem” exercise. Some “poems of the date” are included in the fourth section, but they seemed related to the rest of the section. The writing throughout When a Woman Loves a Man is clever and charming; Lehman devotes much of the energy of the book to writing in received forms. There are multiple sestinas, a difficult form for a poet to master and not be mastered by; some are more successful than others. In an interview with the online journal Drunken Boat, back in 2001, Lehman talked a little about the formation of the poems that would end up in this book: “While I continue to write poems in the manner of The Daily Mirror and The Evening Sun, I am also working on poems that are very different. I’ve been writing in various forms: sestinas, sonnets, a prose poem in the form of a corrections column in a newspaper, a prose poem in the form of a story shorter than fifty words, a series of twenty-six-word poems that recapitulate the alphabet. There’s also a series of biographical poems. So far I’ve completed three: on Napoleon, Wittgenstein, and Freud.”

The re-imagining of the lives of historical characters from Wittgenstein (“Wittgenstein’s Ladder”) and Freud (“In Freud’s House”) to “The James Brothers” were extremely satisfying poems, amusing and thought-provoking. The tone of these biographical poems reminded me of Robert Lowell’s poems on other poets, like Ezra Pound and Robert Frost, in which Lowell imagines his conversations with his famous peers and predecessors. Lehman imagines casual conversations and endearing quirks, both making fun of and commiserating with the humanity of these historical figures. He brings up quotes that display Freud’s predilection for self-aggrandizement but then points out his affection for his dogs; he humanizes Wittgenstein by reminding us of his jokes and his love of detective novels. His observations of famous men could also be read as autobiographical, revealing himself as he wrote about the things he had in common with them.

For those who follow the minefield that is the contemporary poetry world and the politics of the “po-biz,” you will enjoy Lehman’s send-up of that world’s sacred cows. Standout poems include the snarky “Big Hair,” a rollicking and irreverent sestina about Jorie Graham and her infamous hair: “…Jorie went on a lingerie / tear, wanting to look like a moll / in a Chandler novel” (62). I have to say this poem does make me think of the inherent sexism of a world of poetry business that exalts a woman’s looks above her writing — but you can’t feel too sorry for anyone who is a chair at Harvard AND has the kind of hair men dedicate poems to, so I’ll let Lehman slide this one time. “Questions to Ask for a Paris Review Interview” is a great in-joke for those of us who have pored over countless interviews in the Paris Review, only to be mystified by some of the inane questions, which are parodied in the poem:

How do you feel about being labeled a Southern writer?

Let me play devil’s advocate here for a minute.

That split is revealing about America, isn’t it?

When was last time you pulled an all-nighter…Would you like to comment on literary affairs in the Netherlands?

Can anything save humanity?

Does genius vary inversely with sanity?

Do you do any work with your hands? (60)

The humorous effects in both “Questions” and “Big Hair” are heightened by the formal aspects of the poems, the strict rhyme scheme and repetitions. Another in-joke poem that works quite well is a “Poem in the Manner of Wallace Stevens as Rewritten by Gertrude Stein.” His ability to capture the spritely spirit of Stein and combine it with the implacable whimsy of Stevens makes this poem a tour-de-force.

Some poems, particularly in the last section, deal obliquely and directly with the experience of being Jewish. The two poems “Jew You” and “Dante Lucked Out” are very strong, the least glib of the collection – the visceral pain that anti-Semitism can cause is obvious in lines like “you know who’s / behind the Jews? The Jew fucken Mafia in Jew York city” (112). Later in the same poem, he references Allen Ginsburg’s conflicted feelings about his heritage: “and when Lionel Trilling asked Allen Ginsburg why he, a fellow Jew, / had written ‘fuck the Jews’ in his dorm room window, / Ginsburg sighed: “It’s very complicated” (112). In “Dante Lucked Out,” he indirectly references T.S. Eliot’s anti-Semitism by talking about Eliot’s jealousy of Dante’s times, and then the consequences of being Jewish in Dante’s age.

My favorite poem in the book is the title poem. With just enough melancholy to balance out the humor,”When a Woman Loves a Man” deals with compromise in relationships, expectations, and the meaning of love. This longer free-verse poem has something of the character of the poems from Lehman’s previous book Valentine Place, which showcased the irony, the insight and self-deprecation he is capable of. From the middle of the poem:

When he says, “Ours is a transitional era,”

“that’s very original of you,” she replies,

dry as the martini he is sipping.They fight all the time

It’s fun

What do I owe you?

Let’s start with an apology

OK, I’m sorry, you dickhead.

A sign is held up saying “Laughter.”

It’s a silent picture. (8)

The bickering, the casual insults, indicate a relationship damaged over time, eroded by the contempt familiarity can bring. A certain soignée insouciance belies the real emotional heart of the poem. But the last stanza, in which the unnamed man gazes on his lover while she sleeps, is full of images of the moon and stars and fireflies, glimmerings of a still-romantic hopefulness.

I have to note that after years of hearing New York and San Francisco poetry fans clap with delight when their familiar props and personages were name-checked in poems, that I can finally say I recognize the names of people from my hometown, Cincinnati, Ohio, in several of Lehman’s poems. Folks who hale from Iowa City will also recognize names dropped in other poems. Name dropping was always a signature of the New York School, which has been an avowed fascination of Lehman’s; who can think of Frank O’Hara without thinking of the nonchalant inclusion of his circle in his poems? And it’s proof that the poet is social enough to have friends, a sign of inherent humanity. When I read Lehman’s poems, as when I read Tony Hoagland, I can always imagine the poet surrounded by like-minded poet friends drinking and trying to one-up each other.

This is a book for anyone who wants to see Lehman flex his formal-writing muscles, who wants to follow his stories of affection and heartbreak, or his winking digs at the poetry establishment that he is certainly, now, a big part of. If I had one criticism of the collection, it is that sometimes, the wordplay poem’s “raison d’être” seems too slight – like the playful but thin “P.C.” and “Denial.” But overall, there is enough substance to satisfy, and these poems (and their personas/speakers) are unassuming and likable enough to dispel the misgivings of tougher critics than I. How can one resist that voice, which no less than John Ashbery calls “wisecracking but resonant”? Who can resist his modest invitation to see the world through his gently mocking gaze?