Karla Huston

by Phillip Dacey

Turning Point

2004

$17

Thomas Eakins, a native of 19th Century Philadelphia and fairly true to his city (he studied abroad only briefly) is considered to be one of America’s greatest painters. Because Eakins is known for his passion for technical exactness, it should not be surprising to find Philip Dacey using the same precision in this volume. From sonnets (some written as a sequence on one painting) to sestinas and poems built from rhyming couplets, the construction of Dacey’s poems fits the careful attention to detail that Eakins gave the subjects of his paintings.

In “Found Sonnet: Thomas Eakins on Painting,” Dacey reiterates the artist’s instructions for painting:

Before you paint the sitter, paint the chair.

Get things as they are. Make a fat man fat.

Why should we copy Greeks? They copied nature.

The hand shaped right tells how to shape the foot.Make it better or worse — never compromise. 17

Eakins is famous for not compromising, for not flattering his sitters but painting them directly, with honesty and without fuss. Dacey’s poetic stylings address Eakins the man and the painter in the same direct, uncompromising manner.

In the sonnet sequence: “Thomas Eakins’ ‘The Gross Clinic,'” Dacey’s poetic voice describes the painting that earned Eakins criticism for its anatomical exactness. The surgeon’s blood-spattered hand offended many when the painting was displayed at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876. Dacey reports the scene from various points of view, including that of the doctor, the mother of the boy on whose leg the operation is concentrated, a watching gallery of students, Eakins himself and the patient, who appears to be humiliated and befuddled by the process. “For many, I am hardly here, less a young man / than a visual puzzle made of meat.” After allowing Eakins to paint the scene, Dr. Gross explains: “The light on my forehead almost hurts, a weight. / I strove to elevate our profession, prove / we were not butchers.” In the last poem in the sequence, Eakins speaks: “I can be found here at the edge, sketchpad / on my knees, but, really, I am everywhere.”

One of the strengths of this volume is the poet’s use of dramatic monologue, poems in the voice of one character in a dramatic situation-most often a person of historical significance. In the tradition of Browning and the more contemporary poets Ai and Richard Howard, Dacey’s dramatic voices bring the reader face first into the hearts and minds of Eakins the painter, his critics, his subjects. In the poem “Models,” the voice of the prostitute who has been asked to pose is heard in all its wisecracking, streetsmart lingo:

You artists have the dirtiest minds of all.

Look but not touch? It gives me the creeps.

So I’m to pose naked like some piece of marble,

not be a woman? I should call the cops. 23

Even Walt Whitman isn’t immune to Dacey’s musings. In the poem “In Camden,” and in the voice of Eakins, the reader is asked to consider Whitman posing — in the buff, no less! While Eakins’ portrait of Whitman is well known, there is no historical evidence that Whitman ever posed nude, yet the poet asks the reader to consider that it might have happened. And imagine the Great Gray Poet himself, naked and sitting for this artist-all light and shadow, that beard and hair, the vast landscape of his aging body:

It was, of course, the natural thing to do,

so natural we only joked at first,

until one of us, I forget which, said, Why not?

Why not, indeed? Here was the body’s poet,

singing electric, gross, mystical, nude. 25

Dacey imagines that they discussed logistics — the need for light, near a window? But what would the neighbors say? “And then I did not want him to catch cold.” Relaxed and at ease with the painter, Dacey supposes the poet fell asleep. Eakins was famous for his candid, often unflattering portraits and his ability to find the truth in what he saw and the beauty in that kind of honest portrayal. “All I could do was look, / and look as I never had before, seeing / him naked as if for the first time,” writes Dacey, and:

Rather, betrayed into sleep by that lot of him

now more weary than luscious, he’d sunk from his upright

human formality onto the tree

of his naked humanity, and my busy brush

had gone still long enough to let me see. 27

According to the poem, Eakins never finished the painting. He says, he “had seen / the one I wanted, or the idea of it”:

the one in which Whitman’s nakedness doesn’t

challenge us, like a hat worn indoors or out,

but enters us like words whispered at night,

some message about our secret parentage–

“I am your father, I am your mother”–

what a sleepy child might vaguely hear

and never-never fully-understand. 28

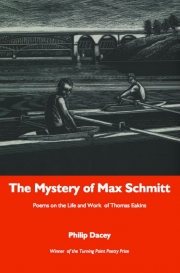

In the title poem in the collection, Dacey again uses dramatic monologue to speak for the people behind the paintings. The voice of Max Schmitt calls from his boat in “Champion Single Sculls” (1871), one of Eakins’s most famous paintings. The narrator, Max, after rowing a single shell on the Schuylkill, speaks of the other boater in the scene: “Tom, / twenty-seven and just back from France.” “Our wakes tell the story, / how we passed each other, / two old friends from boyhood.” Schmitt addresses an unidentified watcher on the shore and says, “Why do we so wound the water / to move forward? The wider the wake, the sooner it will disappear.”

A sculler, I must face backwards

to move forwards,

so that looking over my shoulder

I seem to be moving into a future

that is already, before its time, all past. 45

I wonder if the ghost of Eakins has been looking over Dacey’s shoulder? Does this ghost enjoy seeing himself go to the movies, seeing Max row across the screen, and see Hitchcock make a cameo appearance? One can only hope. In the second poem in this series titled “Eakins Up-to-Date,” the poet imagines the painter leaving the Philadelphia Museum of Art to greet “walkers, runners, cyclists, and idlers” displaying bodies and movements that would please him. Dacey’s narrator considers how the paraphernalia of rollerbladers might gratify him even more than the beautiful girls. Eakins would be struck by the moves of a black skater, crowned in dreadlocks, and wonder exactly how he would paint it, each braid, “thick as climber’s ropes.”

As much as Eakins believed and trusted in the truth of the people and scenes he painted, when finished with this book, the reader will believe and trust Dacey’s narrative voice, appreciate his careful attention to detail, whether rendered in formal, metrical patterns or in free verse. Dacey’s precise and imaginative telling brings the painter to the page — all his frustrations and successes rendered in a true and artistic voice. And like the sculler in Max Schmitt who looks over his shoulder, the reader sees the scenes and the words burning between.

Karla Huston recently earned an MA in English/Creative Writing from the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh. In addition to winning the Wisconsin Regional Writer’s Association Jade Ring for both poetry and fiction, she has received writing residencies from the Ragdale Foundation in both 1998 and 2002. Her poems have earned eight Pushcart nominations. She has published poetry, reviews and interviews in many national journals including Cimarron Review, 5 A.M., Margie, North American Review, One Trick Pony, Pearl and others. A former board member for the Fox Valley Writing Project and the Wisconsin Fellowship of Poets, she teaches poetry at the summer Write-By-the-Lake Writing Retreat. She is the author of five chapbooks of poetry including Virgins on the Rocks, which was published by Parallel Press in November 2004, and Catch and Release, just out from Marsh River Editions.