Joyce S. Brown

by Marilyn Nelson

Louisiana State University Press

1997

$21.95

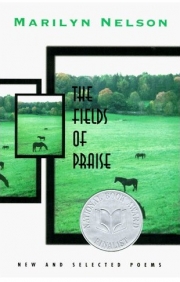

The poetry in Marilyn Nelson’s 1997 National Book Award Finalist collection of new and selected poems, The Fields of Praise, varies richly in both subject matter and technique. In section I, “Mama and Daddy,” Nelson recounts, in conversational poems, poignant, engaging stories of her parents and what they gave her. Her father “was a navigator on B-52s. His crew was a lot like the crew of the bomber in Dr. Strangelove (1964) in which James Earl Jones plays the part of the navigator,” she writes in the notes on the poems. The Tuskegee Airmen poems, she says, are true:

These men,

these proud black men;

our first to touch

their fingers to the sky.

Except for their short lines, many of the poems in this section read like prose. The riveting stories contain racial tensions of WWII – harsh, blatant prejudices to be confronted.

Section II, “Homeplace,” contains what Nelson calls “family history poems my mother’s gift to me and mine to her memory.” These poems are also rather prosy but their intimate, often elegaic tone and vivid details carry them. One poem begins “It’s the ragged source of memory,/a tarpaper-shingled bungalow” and ends:

Oh, catfish and turnip greens,

hot-water cornbread and grits.

Oh musty, much-underlined Bibles;

generations lost to be found,

to be found.

The section concludes with a virtuosic sonnet series, “Thus Far by Faith” is “based on the early history of Thomas Chapel, a C.M.E. church in Hickman, Kentucky, whose first minister, Warren Thomas (born 1812), was known as a slave to preach to mules.” “Sermon in the Ruined Garden” concludes with delightful humor:

Uncle Warren say, Uh-huh: You think you smart.

Well, don’t hee-haw to me about how faith

helped you survive the deluge. Save your breath.

Show me. Faith without works ain’t worth a fart.

People is hungry. Act out your faith now

by hitching your thanks for God’s love to my plow.

The movement of the book from informal to formal poems, and from homey to rather sublime subject matter gives a sense of the progress of an individual life as it matures.

By the third section of the book, Nelson’s poems are “inspired by Giotto’s frescoes about the life of St. Francis,” Mary’s “Magnificat,” “the Book of Jonah,” and Saint John of the Cross. In her notes detailing these poems, she adds, “No, I am not Catholic.”

The final section, “Still Faith,” reveals more of the scholarly Nelson. Here she draws on the work of a Danish poet, Bjornvig, whose poems “since the late 1970s have confronted environmental issues and animal rights. The unbuttoned sonnets in this section were responses to my readings about the nature of radical evil.”

Nelson’s writing is rich in story, philosophy/theology, and language. She moves comfortably from low to high diction and back again. She can write within the strict parameters of the sonnet form; she can write in slant rhyme or in free verse, and knows intuitively which form her subject requires. In all the poems, whatever their form, Nelson’s guiding voice and intellect provide the compelling force. She is moral, loving, visionary, strong in soul. Reading her work is as much a lesson in history and in human nature as it is a lesson in poetry.

Joyce S. Brown appeared in Smartish Pace, Issue 2. She selects poems for the City Paper in Baltimore. Her poems have appeared in The American Scholar, The Tennessee Quarterly, Commonweal, The Maryland Poetry Review, The Christian Science Monitor, and other publications.