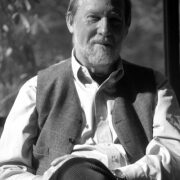

Q&A with Stephen Dunn

Stephen Dunn is the author of eleven collections of poetry including, most recently, Different Hours (Norton, 2000). Loosestrife (Norton, 1996) was a National Book Critics Circle award nominee, and Local Time (William Morrow, 1986) was selected for the National Poetry Series by Dave Smith. His poems have appeared in numerous publications including The Paris Review, The New Yorker, APR, and Kenyon Review. He is the recipient of a 1995 Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Literature. Among his other awards are the Levinson Prize from Poetry magazine, the Theodore Roethke Prize from Poetry Northwest, and fellowships from the N.E.A. and the Guggenheim Foundation. He teaches at Richard Stockton College. (2000)

How did you find out you won the Pulitzer Prize and were you surprised?

Mary Lopes — L.A.

It was leaked to me a little before the official announcement. I was very surprised then. And then not surprised when I should have been.

How do you decide which subjects, events, etc. are worth writing about and which aren’t?

Mathew S. — New Orleans

I follow my concerns and passions, or discover them in the act of composition. The ones not worth writing about are the ones, finally, that I haven’t successfully executed or when I haven’t gotten beyond my initial impulse.

In “A Romance” the figure of the woman is the abstract thinker–“She spoke about the possible/precision of doubt”, while the male figure is purely practical and only makes a non-pragmatic statement in his sleep–“the half-shut eye of the moon.” Another poet might have gone on to attempt some larger comment about this pairing, why have you left the poem as it is? Why is it, do you think, that so many poets (professors) will tell you that poems that are quiet and simple on the surface, must do more, push farther in order to be successful?

Clare — Greenbelt, Maryland

Well, sometimes they might be right, it would depend on how earned the quietness and simplicity is, or should I say how successfully orchestrated it is. In the poem of mine that you mention, I think that I felt that the juxtapositioning of the couple’s musings sufficiently suggested the nature of their relationship, or suggested the mystery of it.

I often tell my students that epigraphs are useful for particularly cryptic poems as a way of grounding their readers. I’ve noticed in reading _Different Hours_ that the poems in section three particularly have epigraphs or dedications. In your opinion, for whom is that useful, the poet or the reader?

A Professor — New York

Epigraphs are useful for the poem itself, or should be discarded. That is, they either contribute to some desired effect or they don’t. At best, they’re part of what constitutes the fictive. Of course epigraphs might be useful for getting a poem started. But most of them should then be deleted.

Could you please give me a short list (5 to 10) living poets that you recommend people read? I’m not asking you to pick the 5 or 10 best (and thus possibly offend a fellow poet), but just a good place to begin?right now you’re soundly in my top five. (followed by Carol Ann Duffy, Mark Jarman, Tony Hoagland, and Stephen Sandy—not that you asked!) Thanks for answering and thanks to SP for providing the opportunity!

Parker — Spearfish, South Dakota

I’ll make a short list of non-Americans for you, and keep the American list to myself. Szymborska (sp?), Carlos Drummond de Andrade, Zbiginiew Herbert, Anne Carson, Yehuda Amichai.

How old were you when you wrote your first poem and do you remember what caused you to write it?

Deb — Medical Lake, Washington

I was probably in high school. And it probably was a little ditty to make some girl love me. But I didn’t start to write poetry seriously until I was in my mid-twenties.

There seems to be a real cast of death and dying over your last book of poems, do find this or am I miss-reading you? And why the cast of death and dying?

Brent Star — MSU

If there exists such a cast in the book, it’s because I was writing those poems as I neared sixty, the age that no male in my family had reached, and which therefore I never expected to reach.

I don’t dislike learning about poetic forms, but most of it seems more like a history lesson and not something that’s important for my growth as a poet. How important is it for a young poet to learn different poetic forms and why?

Erica — North Brunswick, New Jersey

Think of it as acquiring the tools of your trade, which you may or may not choose to employ. A carpenter doesn’t always use a drill, though it would be disastrous for him not to know that it exists for him, and might facilitate what he wants to accomplish.

In one of your essays I’ve read, you mention poems that you’ve recently been reading aloud to people, are there a few poems you’re currently recommending people read out-loud? I like reading David Kirby’s poems out-loud in the shower. Would you like to read one of his poems out-loud?

Angel — Miramar, Florida

I hope you have Kirby’s poems memorized. And yes, I do enjoy reading his poems out-loud or to myself.

Why aren’t English poets read in America? Are American poets popular in England? Do your books sell anywhere besides America?

Rachel Roberts — Rochester, NY

I can’t answer those questions with any authority, except the last. No, they don’t, as far as I know, sell very much outside of the U.S. But of course poetry doesn’t sell very much in the U.S. either, whether it’s English or American.

Who is your favorite living critic?

Deborah — Baltimore

I don’t have one.

I often hear fellow MFA students berating the quality of poems being published in major literary magazines these days, what do you think about the overall worth of contemporary American poetry? Do you think a lot of schlock is being printed even by those so-called “big name” poets?

Brandon — Iowa City

At any given time in any culture most of the poems in print will be mediocre. Don’t worry about it, it’s a given. Just keep an eye out for what’s wonderful.

Are you married to a poet, if so, what is that like?

K.C. — Rancho Cucamonga, California

No.

Smartish Pace has published some poets, like Michelle Boisseau, Stephen Cushman, Marilyn L. Taylor, Rick Alley, and John Grey, who wrote excellent-first-rate-poems, yet it’s difficult for me to find their poems elsewhere. What does it take to “make-it big” as a poet? What besides great writing? Because these folks should be making it and sometimes I read big name poets (yourself NOT included) and I think, “who the hell buys this?” Thanks for answering, I’m a big fan of your work, Carry.

Carry — Muskogee, Oklahoma

It’s counterproductive to worry about such things. Just live with your work and the work of those poets you love.

I’m always surprised by what poems my students love and which ones they complain about. Which poets do you find are the best for teaching college-level workshops?

B. — Berkeley

How long does it take before a poem feels finished after you write it? Do you typically go through several stages of revision, or is it a fairly quick process for you?

Laura Pickens — Mobile, Alabama

Several stages of revision. Like everyone else, I often delude myself that a poem is finished.

Your poems often seem deceptively (and beautifully) simple. Are there particular qualities that you strive toward as you write and revise a poem?

Trent F. — Billings, Montana

To answer you properly would take a long time. In short, though, a clarity that serves complexity. As Auden said, “the clear expression of mixed feelings.”

You wrote several poems about the Oklahoma City bombing that really connected for me. Do you worry that poems about “current events” will seem dated as time goes on?

Barbara — Rapids, Wisconsin

You write the poems that you need to write. All other concerns are tertiary. Do you think that poets and other artists have a responsibility to respond to events and tragedies like the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center? No.

Has winning the Pulitzer (or any other prize) had an effect on your writing or how you think about your poems?

Steve Anderson — Milwaukee, Wisconsin

No.

What do you like to read? Are there any poets or artists that you feel especially akin to?

Billy — New York

Yes, many. If yours were the only question, I’d attempt an answer. But it seems too big a question to give a partial answer to.

Do you have a ritual or routine you follow when you write?

Max D. — Southern California

I need a good chair in a quiet room.

You’ve mentioned that you feel your most recent collection of poems is your best. Do you feel this way each time a collection comes out or is this one special? How do you think about your growth as a poet (e.g., series of stages, leaps forward followed by setbacks followed by more leaps)?

Brenda Lane — Provo, Utah

I’m not sure anymore if I think Different Hours is my best. It may be. But perhaps suffice it to say that I have favorite poems from different collections. And I suppose I feel that my poetry has progressed in a series of stages, a supposition that would take too long to go into here.

Your poem “John & Mary” is really great. The epigraph at the beginning is from a freshman’s short story. To what extent do your students affect your writing?

Stan Philip — Summerville, West Virginia

Thank you. And not a great deal.

If you could give one piece of advice to young poets, what would it be?

Rainer — La Crosse, Wisconsin

Take your enterprise as seriously as other would-be artists do. No short cuts. Try to be as engaged and as disciplined as, say, a violinist or a dancer would.

One thing I’ve noticed about my graduate program is that there seems to be a schism between serious study of poetry (relegated to the MFA program) and serious study of literature (which is the norm). Do you think that’s true in academia? What, if anything, can be done about it?

Jackie Dorsey — New York

Too big of a question for me to answer here. On a related note, how do you think MFA programs have affected the quality of poetry being written in the U.S.? Hard for me to say, except that the genuine poet is rare. I keep an eye out for him or her. The rest I don’t worry about.

What’s the last book of poetry you read?

Lisa Turner — San Diego

Anne Carson’s THE BEAUTY OF THE HUSBAND.

Do you still get excited after all these years when a new book of yours is released? Or when a poem appears in a magazine? I really like “How by Design” in Smartish Pace. Thanks.

Mr. Planter — West Warwick, Rhode Island

Less and less, I’m afraid. In the case of a book, more like a quiet satisfaction.

Wordsworth once said something along the lines of: poetry is emotion recollected in tranquility. Is that a bunch of bullshit or what? What does poetry mean to you?

Bart Nelson — The Hills of Virginia

Among the many things poetry is, Wordsworth’s statement ranks high in my estimation.

The poems of yours I’ve seen in journals lately, which on occasion you’ve grouped under the title of “Local Visitations,” have distinctly longer lines than most of the poems in your earlier books, such as LOCAL TIME, BETWEEN ANGELS, LANDSCAPE AT THE END OF THE CENTURY. I can see why you might use longer lines, more “paragraph”-like stanzas, for this subject matter, but my question has to do with performance: when you read these poems in public, do you read these lines differently than shorter-lined poems? If so, how are they read differently: faster? slower? more or less pause or attention at the line-break? Thanks, Bill Wenthe

William Wenthe — Lubbock, Texas

Interesting question. I haven’t read them much in public, but when I have I haven’t noted much of a difference. They seem held together by what I consider my voice.

How has your enjoyment of writing and completing poems changed from when, say, you first began writing poems, and when you write poems now?

Bill Danpier — London, Ontario

Poems seem a little more difficult to write now. I can’t count on my ignorance as much as I once did.

Have you ever regretted becoming a poet versus a novelist or playright? Have you ever daydreamed about what it might have been like if you’d have chosen a different path? And one more question if you’ll allow me: if you had not found any success early on as a poet, or less success than you did find anyway, do you think you might have tried your hand at something else completely? And what might that have been?

Tom Hughes — Cleveland

I’ve written a novel, so I’m quite sure that poetry has been the right course for me. And I was, for a while, on a different path, working for a corporation, so poetry seems like a very chosen path for me. And of course, if poetry and the teaching of it hadn’t worked out, I might have done any of the many things people do to make a living. I might not have become an accountant, however.

The American public has a vexed relationship with the arts. Obviously they need, or at least want, to be involved with them, and care deeply for them. The former proved by music and movie tix sales, and the latter by a public outcry such as the one against the Taliban’s destruction of the Buddhist statues in 1999. As a contemporary artist in an under appreciated field, how do you feel about this relationship between the public and the arts, and about the “art” that does find its way into mainstream acceptance vs that which does not? And thanks so much for your time.

Erik — Baltimore

In one sense the under appreciation of poetry in the U.S. frees the poet to do whatever he wants. In another sense, he can do what he wants because what he does doesn’t matter. No Mandelstam-like repercussions here for writing an important anti-government poem. But it’s important for me to write AS IF everything I write matters. And AS IF I have a concerned, intelligent audience. To not turn my back on the willing, intelligent reader as much contemporary poetry has. The poet needs to make gestures to the willing intelligent reader. That same reader must make serious gestures of attentiveness to the poem. As a follow up to my first question, what are your reactions to the comparative success enjoyed by Billy Collins? (which, of course, has been legitimated by his recent appointment), who is obviously a poet of great erudition and style, but considered by some to be overly accessible. He is a poet of erudition and style, a very good poet. The people who worry about him being “overly accessible” don’t know the pleasure or the difficulty in allowing all your moves to be conspicuous, like a good dancer’s. They are the people who always confuse seriousness with solemnity, and who confuse depth with the obfuscatory.

I’m a sports fan and a lit student. My girlfriend, who I live with, can’t understand how I can thrill to the high art of Henry James in one moment, and the next be a frothing lunatic before a televised, sensationalized football game, which to her perception is devoid of all taste. I try to explain that football, and baseball, and basketball . . . ARE (or can be) great art, but she won’t see. So when I came across your writings on basketball and poetry in “Walking Light” I was ecstatic. Now, even though se remains unconvinced, I have more (and better) ammo in the ongoing argument, and food for thought re athletic performance and the performance of writing. Just wanted to say “thanks” and see if you had any other thoughts on the subject.

Christopher — Houston

Don’t push your argument too far. There may be similarities between sport and writing, but there are more dissimilarities. My guess is that if you acknowledge the dissimilarities you’ll find yourself being more persuasive.

I divide my “creative” time between writing and playing drums, and I have a strong sense of rhythm that I bring to my writing–this, most of the time, is a source of pride for me. Sometimes, though, I can be so committed to the rhythm of a piece that I find myself hindered. What do you think are the similarities and differences between musical rhythm and the rhythm of poetry or prose? In writing a poem, do you ever have a beat in your head that is reduced to musical terms (waltz, swing . . .) as opposed to poetic ones?

Mauro — Detroit

Remember that Emerson said that he wasn’t after meter, but a meter-making argument. In other words, the emotion and the idea find their rhythms, and vary them as is necessary. Yes, if you’re overly committed to a rhythm that will show in the piece. It will have the ring of the inauthentic.

Do you feel like you work out poems of your own when you are teaching others to write? or that teaching affects your writing in any specific way? Or do you make a conscious effort to keep writing and teaching separate?

Kellie Klaswicz — Decatur, Illinios

Not a conscious effort. They just are very separate. Perhaps working on the poems of others has over the years made me a better editor of my own work. Not much more.

My wife and I have separate shelves for our books. That is, one set is for her books and the other is for mine. While I have substantially more books, there isn’t a book on her shelves that she hasn’t read. I love to read books as much as she does, but I also love to HAVE books, and sometimes it will be years from the time I buy a book to the time I read it entirely. Have you read all the books on your shelves?

Byron Lucas — Boulder, Colorado

I actually believe I have.

Stanley Kunitz is a great poet. Is Billy Collins all that? I just don’t get it. The only thing positive about Billy Collins becoming Poet Laureate is that it gives me hope that I too could make it! There’s better “stand-up poets” at the local comedy club.

Darden — Newport News, Virginia

Why would you want to “make it” in a manner you don’t approve of? Your statement damns you. You need to cultivate an awareness of what earned simplicity is.

Obviously it’s every serious writer’s dream to win a Pulitzer. How has your life changed since you won yours?

Linda C. — Tuscaloosa, Alabama

Not too much really. Most of my habits and friends were in place. That makes it just a tad bit harder to ruin your life.

If I remember correctly, you began writing poetry in your early-mid twenties (?) At what point, though, did you consider yourself a poet?

John Tredmon — Madison, Wisconsin

Well into my thirties I would say “I write poetry” rather than “I am a poet.” At a certain point, I think, I began to embody my poems, and they started to feel like mine. I suspect somewhere around my third book I felt sure I was a poet.