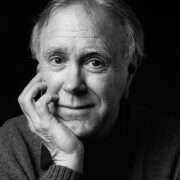

Q&A with Robert Hass

Robert Hass was born in San Francisco on March 1, 1941. He attended St. Mary’s College in Moraga, California and received both an MA and Ph.D. in English from Stanford University.

His books of poetry include Time and Materials (Ecco Press, 2007), which won the 2007 National Book Award; Sun Under Wood: New Poems (1996); Human Wishes (1989); Praise (1979); and Field Guide (1973), which was selected by Stanley Kunitz for the Yale Younger Poets Series. About Hass’s work, Kunitz wrote, “Reading a poem by Robert Hass is like stepping into the ocean when the temperature of the water is not much different from that of the air. You scarcely know, until you feel the undertow tug at you, that you have entered into another element.”

Hass has also co-translated several volumes of poetry with Czeslaw Milosz, most recently Facing the River (1995), and is author or editor of several other collections of essays and translation, including The Essential Haiku: Versions of Basho, Buson, and Issa (1994), and Twentieth Century Pleasures: Prose on Poetry (1984).

Hass served as Poet Laureate of the United States from 1995 to 1997 and as a Chancellor of The Academy of American Poets from 2001 to 2007. He lives in California with his wife, poet Brenda Hillman, and teaches at the University of California, Berkeley.

Do you view yourself as a California poet? If so, in what way?

Dacey — Boston

Robert Hass: Well, yes. I grew up in California. I live there. I was influenced, at different times, by West Coast writers like Robinson Jeffers and Kenneth Rexroth, Robert Duncan and Gary Snyder, some of whom I read more intensely than I might have, were I born in Wisconsin. And, to some extent, the place has been my subject matter.

In your poem “Meditation at Lagunitas” you write, “a word is elegy to what it signifies.” I have discussed this line with a number of colleagues, and we have yet to come to consensus for interpretation. I wonder if you could clarify your use of the word “word” — do you mean the written or the spoken word, or both? If written, elegy takes on a particular tone suggesting the loss of something “there” when transcribed to the page. If spoken, the loss seems more nostalgic. Thanks for your response.

Stan — Maryland

Robert Hass: I don’t think I thought about the distinction between the written and spoken word when I was writing that poem. I think I meant the word-spoken or written-as a marker for a class of things, and about the proposition that the fact of its being a symbol and a marker both points to the thing and emphasizes our separation from the particulars that compose the class of things evoked. Something like that. Somebody put it, I think, that our first purposeful utterance is a cry and it means “no breast” or “breast,” or both at the same time. And yet-in my experience of language, I now think, and I think I was thinking then, it is simply not the case that a word is a marker, or a sound or set of symbols representing a sign. That functional definition simply doesn’t cover our actual experience of language which is much livelier than that, more radiant. I think I use the word “numinous” in the poem. Does this answer the question, Stan?

Why do we have to wait so long between your books?! I love your work and I’m curious to know why you take so much time between the publication of your books.

B.T. — San Diego

Robert Hass: Thanks. B.T. I wish I knew. I’m slow. I’m easily distracted. It is a terrible struggle for me to make time for work, the stretches of it I seem to need to get concentrated work done. —I mean, I’m always working on something, translations or prose or some public project, but I tend to get pulled in many different directions. My friend, the philosopher Richard Wollheim, once described himself as a person inclined to treat a mild request as a command. I recognized that description. For example, here I am answering these questions instead of writing. Though I had the idea that it would help me to focus on my central task.

Are there some folks that were particularly encouraging or helpful in your special projects, as Poet Laureate, involving literacy and the environment?

Rachel — Washington, DC

Robert Hass: Many. In an earlier version of these answers that my computer ate, I listed them all. I won’t do it again. But there are many people some of whom I got to know and some I didn’t, in the Library of Congress and in the non-profits and the schools, in the Department of Interior and the EPA, who are doing great and inspiring work.

How has translating poetry into English affected your own writing?

Carl — Jackson

Robert Hass: Well, it’s taken time. Translation is a way of studying writers or individual poems very intensely, so you absorb their energies, ideas, rhetorical strategies way below the level of consciousness, I think, where they become part of your own repertoire of responses while you’re writing. Auden in his essays evokes a phrase from Shakespeare–“the dyer’s hand.” Translators probably get soaked in the stuff they translate.

“Meditation at Lagunitas” has been one of my favorite poems since I first read Praise back in 1985 (one of my favorite books). Can you talk a little bit about what inspired the poem, or how it developed, how it came to be? What does it mean to you?

Jeneva Stone — Bethesda MD

Robert Hass: I think, Jeneva, the poem describes pretty accurately the terms of its inspiration and development. I mean the immediate experiential background–‘in the voice of my friend,’ ‘there was a woman I made love to.’ Back of it also, probably an irritant from my readings, not extensive, in various Platonisms–“the idea, for example, that each particular erases the luminous clarity of a general idea.” I am not sure I understand what you are asking when you ask what it means to me. I am not sure whether you mean by “it” the poem, my having written the poem, or the existence of the poem in the world. And I’m not sure if you are asking how I would interpret it–that idea of meaning–or how I feel about it. I think the poem is pretty much my interpretation of the meaning of the poem. And I feel about it the way I feel about most of my poems. When I revisit them, I mostly see their defects first. If I read them aloud, or read them to myself aloud in the silence of my head, I get back inside their rhythms, which is where a lot of the labor and attention is for me, and I sometimes like them better.

I am interested in knowing what drew you to the prose poem form in Human Wishes. Also, do you think that the experience of writing those poems influenced the poems in Sun Under Wood formally, and perhaps thematically as well? If so, how?

Paul — Washington, DC

Robert Hass: I talked about this at some length in an interview that was printed some years ago in the Iowa Review, if you want a fuller account, Paul. As I recall, I was writing the peice that became “Museum” in Human Wishes and I couldn’t find in the rhythms of the verse a way to describe the reciprocity between the young couple I was trying to describe. So I turned aside to write it out in prose to clarify for myself what I was seeing. And once I felt like I’d gotten it in prose, there didn’t seem to be a reason for trying to translate it back into verse. I had been working on some of the essays in Twentieth Century Pleasures around this time, and I found that writing them I would sometimes labor over the shaping of particular paragraphs in the way that I work on poems. So the two impulses seemed to fuse for me at the moment, and I became interested in the idea of the paragraph as a form. A phrase came into my head–the name of a posthumous book of essays by Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “The Prose of the World”–and that gave me a push also. Later, looking back on those pieces, I came to think that I had begun writing in prose to avoid the deeper engagement with what I was feeling that verse would have required. Prose seemed a cooler medium. And in Sun Under Wood, particularly in “My Mother’s Nipples,” it’s true that the things we can say in verse and the things we can say in prose became a theme.

Images paired with abstractions often appear in your poetry. Generally, the abstractions stop me. Any suggestions as to how to “read” the abstractions and not give up on what may appear to be too cerebral?

charles cantrell — madison, WI

Robert Hass: Charles, I wrote and lost a long answer to this question. So this will be shorter. I think images paired with abstraction appear in most poetry–if you mean by abstractions words that refer to general categories of ideas like “justice” rather than words that refer to general categories of things like “tree”. Your question implies that abstractions are more cerebral, I guess you mean less rooted in the senses, than images. And there are other categories of noun and verb–is “word” more cerebral than “tree” but less cerebral than “justice,” etc. This is all mixed up in English with the way the language itself mixes up its Latin and Germanic roots. “Tree” from Aglo-Saxon, “justice” from Latin. If I had an example of what you were troubled by, I could answer more usefully. But poetry can do a range of things. There are poets who think in their poems in the whole vocabulary of English and others who rely pretty much on tactile images. Poetry certainly needs body, but it can get it from the music of its rhythms; it doesn’t always have to be sticking to a picture language to stay tactile. Examples are better than arguments. My arguments would be in the general direction of some poems of George Oppen and Wallace Stevens.

I’m very interested in reading more contemporary Polish poetry. I suspect you have some favorites besides Czeslaw Milosz, who might they be? Adarn Zagajewski? Wislawa Szymborska? Some lesser known (to American’s) Polish poets? Thank you for any guidance you can give me.

Chris — Baltimore

Robert Hass: The most important Polish poets of the mid-twentieth-century generation who are available in English are Milosz, Symborska, Tadeus Rosewicz, and Zbigniew Herbert. A lot of Poles think that Herbert is their most important poet. The other poets whose poems can be found are Anna Swir and Alexander Wat, both translated by Milosz. There is also his anthology Post-War Polish Poetry. In the generations after them, only Adam Zagajewski’s poems are widely available in English. But there is an anthology (which needs to be updated) called Humps and Wings which will give you a sampling of that generation. And I think there is an anthology in English just out or coming out of the younger generation–the post-Communist generation–of Polish poets. The crucial historical figure in Polish poetry is Adam Mickiewicz, and there is one very good translation of a part of his major poem “Pan Tadeuz” by the English poet Donald Davie. It’s called “The Forests of Lithuania,” I think, and it may be in Davie’s Collected Poems. To see what else is there, you might look at Milosz’s History of Polish Literature.

I have a question about your form. How do you decide when to use stanza breaks in your poems? The form seems much more organic, and often broken more at places that feel right with the tone or mood, but I wondered if there was a particular method that you’ve developed for your own work. I would say I have a strong understanding of poems which follow a more consistent free verse pattern, tercets, quatrains, etc. but I’m interested in understanding how one embarks upon a form such as your own. Thanks. I’m a huge fan of your poetry. I saw you read a few years back at the University of Michigan. It was a great pleasure!

Michelle Sorgen — California

Robert Hass: Thanks, Michelle. Big question. Stanzas in English poetry were originally a function of the rhyme scheme—I mean before scribes used space on the page to indicate a stanza, you could tell by sound when a stanza had ended and another one begun. The convention of giving written down poetry a lot of white space on the page made the other part of the convention of the stanza. When poets began to do without rhyme, the function of the stanza was no longer self-evident and it got expressed by the convention of white space. But what was it for? Whitman was the first poet in the English language, as far as I know, to deal with this problem. It looks like he mostly–in “Song of Myself”–used the stanza as a paragraph is used in prose (but what he does is actually more complicated than that) and on a different scale in his short poems also. What he doesn’t do is impose a fixed pattern–so many lines to the stanza–and not doing that is what people have come to call “organic,” I guess. That is, it is just as much an artist’s decision as a fixed stanza pattern is, but it gives an appearance (it may be the case) that the content is determinging the stanza length and so it appears more natural. I think I probably begin there. The fixed pattern stanza conveys an idea of order. It gives the poem a more Apollonian look on the page.

Many people describe the lineage of contemporary poetry as deriving from either Eliot or Williams. Do you see yourself as a decendant of either poet?

Lisa — Greenbelt, MD

Robert Hass: Of both. I think the actual influence of Eliot was more immediate. I read him, or at least a few poems, intensely from high school on. The indirect influence of Williams–of his free verse, of the realist project–was probably much deeper, though I don’t think I really studied Williams until I was in my forties. I think of the Eliot line as the one developing out of symbolist poetics, I guess, the technique in “The Wasteland,” “Prufrock,” “Sweeney Among the Nightingales,” even The Four Quartets, is, roughly expressionist.–“I should have been a pair of ragged claws,” “And fiddled whisper music on those strings” etc; also there is the dramatic gift in Eliot, the people in his poems have voices. By contrast, I guess, the people in most of Williams are seen in snapshots. I think of Williams and Whitman together in their realism, their use of local materials, something pragmatic in their approach to people and life.

Do you have any advice for someone who has an MFA (Goddard 1977) and was one of your students, has two chapbooks and is looking for a teaching position, with eleven years teaching composition but would like to teach creative writing.

charles cantrell — madison, wi

Robert Hass: Hi Charles. I wish I had some advice for you, but I don’t. I don’t know much about the job market. But I wish you luck in finding the chance to teach creative writing. I imagine it is a matter of applying for jobs when they come up.

What would you say is the difference between “My Mother’s Breasts” and say some of Lowell’s family poems? Why do you think some of his poems get labeled as so-called “confessional” and your poem doesn’t? Is it a matter of “tone”? Or how one sees ones relation toward both the natural and social? Finally, as you discussed in the Hopwood lecture, family is a subject that we as Americans are obsessed with. My question is, do you think it’s finished as a subject in American poetry as some think?

Billy Reynolds — Kalamazoo

Robert Hass: The main difference is that I was very much aware of Lowell’s poems. The term “confessional” probably has limited usefulness. I think it was intended to indicate on the one hand poems dealing in intimate personal materials (confession, as in True Confessions magazine) and on the other poems that courted something like the sacramental (or psychoanalytic) idea of confession, a confession of sin or a narrative of trauma, as a form of healing. (Louise Gluck in her book of essays writes about the difficulties of this second approach with its presumption that the narrator of trauma is, by definition, an heroic survivor; her point is that people who are damaged really are damaged.) Lowell was doing something odd and new in Life Studies. People had always written about family relations and also about all kinds of human behaviors, but they mostly did it at a remove, through myth or the framing of fictional narratives of one kind or another. I think all the masking among the modernists–Prufrock, the voices in the Wasteland, Pound’s various masks, Crazy Jane and other masks in Yeats–led more or less directly to an idea of unmasking in Lowell’s generation, also in Ginsberg, especially in Kaddish, in the next half-generation. Lowell, of course, felt that he had in his family and its lineage an historical subject. He’s said that Faulkner was a sort of model for this. The Lowells and Winslowes were representative of a region and a culture in the way that Faulner’s Sartorises and Compsons–fictionalizations of his family history were–so there was this other agenda in Lowell (and also for that matter in Ginsberg; his mother is also, in the age of the Rosenbergs and Cold War paranoia, a representative American figure). All very interesting—anticipated by Williams in his “Adam” and “Eve” and his other family poems. So there are really at least two separate subjects here that Lowell connected. Family history as subject matter and private life-meaning sexual life and family strife, money, marriage and divorce and illness, scandalous behaviors, the things that people are private about. Lowell took up both in a way that lyric poetry, as far as I know, never really had. Surprising–as I remarked in that Hopwood lecture–because it is such an obvious subject. And there’s been as you notice a turning away from it, as the daring materials of the 1950’s became the daytime TV of the 1980’s and 90’s. It has come to seem part of American narcissism, of the self-absorption of consumer culture. So poets, mostly, have changed the subject. I find myself–or found myself–turning to those materials in my own life to understand certain things, I guess. I was mainly aware, writing “My Mother’s Nipples,” that this was going to seem to many people very tired subject matter. I’m not sure how that affected the writing–the poem is partly about the way it teases and avoids its subject, until it gets down to it–except that I was aware that I disliked the kind of poem (or prose) that wanted mainly to say look what happened to me. Dostoevesky said that the trouble with Turgenev was that if he wrote about a man being hanged he did it by describing the tear in his own eye. Something like that. Is the subject finished? I don’t see how it could be, but it is apt to show up in new forms.

First, thanks for your poetry. I’m probably taking advantage of the offer to ask “a question” by my request, but having fallen in love with the way you use words, especially your poem, “Meditation at Lagunitas,” I’m curious to learn your responses to the Bernard Pivot quiz, made famous by James Lipton of the “Inside The Actor’s Studio” show on the Bravo TV channel. So here goes. Robert Hass, what is your favorite word? your least favorite word? What turns you on? What turns you off? What sound or noise do you love? What sound or noise do you hate? What profession, other than yours, would you like to attempt? What profession, other than yours, would you not like to participate in? Finally, if heaven exists, what do you expect to hear God say when you arrive?

Susan M. Williams — Nashville, TN

Robert Hass: What is the necessary word?

What are the least sufficient words?

What turns you in?

What turns you out?

What species of New England bog berry do you love, regret in the pulp and the sky ashy?

What animal insolence, what bell of what round in the contest between anguish and delight provokes you?

What feather of the winter cardinal would you like to attempt?

What taxi cab meter, measuring the fare uptown toward coffee con leche or the hurt dance of recalcitrant marionettes would you not like to participate in?

Finally, if poetry exists, what do you expect the grass to say, Susan?

“Sunrise” is one of my favorite poems, partly because of the moves between grand ideas (birth) and specific images (deer at creek). Also, the sound and rhythm of the poem is extraordinary. I notice in later poems, your vocabulary is less dramatic, less grand, though the ideas are still weighty. Do you see this difference and can you comment on it?

Brittany, — Alexandria

Robert Hass: I’m glad you like that poem. It’s true that my usual manner is plainer. I think this one began in my mind as an homage to Hart Crane and to the Neruda of the Residencia poems. I wanted a denser, grander idiom, momentarily. It comes back a bit, this style, in “Thin Air” and “Between the Wars” and in some passages in “Berkeley Eclogue.” I think.

I was reintroduced to your poetry this past summer in Iowa by Bruce Bond who was teaching an advanced poetry workshop. Since then I have ordered several of your books and have been reading and rereading your poems. I am having difficulty with a section of one poem from the book Human Wishes. In “On Squaw Peak” I have difficulties with the lines that begin with “You were running” and end “or simply turn away.” It is the identity of the people that gets me off track. I enjoy the poem so much that I would like to be able to follow all of it.

Jean Shepard —

Robert Hass: Thanks, Jean. Let’s see. The person addressed in that poem, the “you” is evidently a friend and colleague of the speaker. “We had to teach poetry / in that valley two thousand feet below us,” he says. And–in the awkward manner of 2nd person poems, he characterizes the “you” to herself. Those are the lines you were wondering about–

You were running–Steven’s mother, Michael’s lover,

Mother and lover, grieving, of a girl

About to leave for school and die to you a little

(or die into you, or simply turn away)

–and they are simply an attempt to describe the situation of the “you”: mother of a boy named Steven, lover (perhaps wife) of a man named Michael), mother also of a daughter about to go off “to school,” college maybe, or boarding school, a loss the “you” is mourning. The three forms of that loss the speaker imagines–a going away is a kind of dying–people “die into” us, that is, we absorb then as we lose them–and kids, going off to school, to their lives, simply–some of them some of the time–turn away from their parents. I was trying to do a little domestic riff on complicated, ordinary feelings, and didn’t mean for it to be mystifying. The poem is very much an homage to Wordsworth and to the conversation poems of Coleridge, but especially to Wordsworth who often addresses his sister Dorothy in his poems. I had some strategy or model like that in mind as a way to muse over the issues the poem muses over.

Do you ever think how your writing may have been different if you hadn’t spent years teaching poetry to young writers? If so, in what ways do you think things could have turned out differently?

David — Baltimore

Robert Hass: I don’t know, David. I didn’t teach writing until after I’d written my first book of poems and then for about ten years I taught a night school open admission poetry class once a week and had a regular academic job during the day teaching literature and humanities courses at a small liberal arts college. I loved the night school class because it was a chance to talk about poetry and be involved with it. This was the stretch in which I was working on my second book and also writing prose about poetry. I would teach in summer workshops and I taught in a non-residential MFA program which was really a correspondence course, but I didn’t regularly teach creative writing courses until I came to UC Berkeley in 1989. So I’d written three of my four books of poems before I was regularly employed teaching creative writing. I do think about what my writing might have been like if I’d tried to make a living as a writer instead of a teacher. The truth is, to be an artist in America, most of us have to try to work at two full-time jobs, and it takes a good deal of juggling one way or another.

How, and when, did you become friends with Czeslaw Milosz? What has his friendship meant to your writing?

Christopher — Georgia

Robert Hass: I started reading Milosz when I was still in college, I think, or just after. I read the prose book, The Captive Mind. And one of my friends from grammar school and high school did graduate work in Slavic languages at Berkeley and studied with him and talked to me about him in the late 60’s. I met him sometime in the mid-70’s after I moved to Berkeley. I was very curious about his untranslated poems. I had no idea then how much of it there was. I started to work on it in the late 70’s and over the years we fell into this long collaboration on getting his work into English and became friends. It’s been a very rich thing for me, living with that body of work, and our friendship a great gift. Czeslaw can be very funny and very good company. And one is always aware of the richness of his experience, also of the terrible task of witness he undertook.

This may be an odd question, but it is a question that I have always been curious about. What is the role / function of the semi-colon in poety? Thank you for your time and your amazing work.

Tim, D — Tempe

Robert Hass: Interesting, Tim. My wife, Brenda Hillman, is a poet and she’s written a wonderful essay on punctuation in poetry, which you will certainly want to look at. It’s in a book called By Herself, edited by Molly McQuade and published by Greywolf. My own sense–without having thought much about it–is that the semi-colon has the same function in poetry as it does in prose. It’s used to bring together and to separate independent clauses in a way that indicates there’s more relationship between them than between two wholly separate sentences. But there must be many other imaginative uses of that broken-looking little mark.

I heard you deliver a wonderful lecture at Sewannee a few summers ago on the Yiddish and cultural influences and the sense behind the sounds of Gertrude Stein’s poetry. Is that lecture/material available in print or one the web?

Cynthia — Baltimore

Robert Hass: It’s not, Cynthia. Thanks for asking. I’ll write it at some point and your asking is a useful spur. There is an essay on Stein’s “Yet Dish” that I read and that you might find interesting, by–this isn’t going to be very helpful–a critic and poet whose first name is Maria who teaches at the University of Minnesota. I’m not home, so I can’t help further with this reference, though I could if you tried me this summer.

Campbell McGrath wrote, “literary magazines are the most authentic forum for contemporary poetry.” Do you agree? What exactly do you think he means by this? Or what would you take this to mean?

Nu — Towson, MD

Robert Hass: I don’t know what he means by “authentic,” Nu. Literary magazines are certainly where most poetry in this country first sees the light of day and where issues of style and subject get played out. Campbell McGrath teaches in Miami. I expect he’d tell you what he meant if you asked him. At Florida International University, I think.

Do you have a formula you return to when faced with dry spells (I hate the phrase ‘writer’s block’)? At such times do you read more books or poems? Do you force your way thru it, just keep writing? Do you take long breaks from poetry?

Sam — North Shore, Chicago

Robert Hass: I do seem to take long breaks, Sam. Usually when I get busy with other kinds of tasks. And I’ve tried different things over the years, the least effective of which has been just to wait. I’ve worked at translation, kept journals, set myself tasks (a paragraph a day that is the equivalent of a photograph, four lines of verse about this or that) I could perform with my will.

Could you share about juggling family life and writing? Has the balance you’ve made between the two worked out OK for you, or has it been a frustration? It seems like the best writers I know personally have difficult family situations. For me it’s an interesting problem. Does one’s family situation influence one’s writing, or is it that one’s writing influences one’s family situation? Of course both are true, but I guess I would like to hear your take on, lets call it the correspondence, between these two things.

Mark C. — Columbus OH

Robert Hass: It is, of course, difficult, Mark, to juggle family life and writing. Especially because it’s not really possible to make a living as a poet (unless you are one of a handful of songwriter-performer-poets). A couple of poets make livings as novelists, but most novelists don’t make livings as novelists, either. So, to be a writer in America, one needs to work hard at two jobs. The third part of that is family life. And since one has to show up for work the conflict occurs in the demands of writing life and family life. And then there is everything else, friendship, other interests, politics, citizenship, spiritual life, adventure. Kenneth Koch has written a poem which remarks that you can have art and love in your life, or art and friendship, but that you can’t really have all three. When I was beginning to write and beginning to raise a family, I so loved being inside the rhythms of family life and parenting, that it was mostly nourishing to me and it also gave me a subject matter. It was what made up the texture of my days, what gave me a life to think about. And, of course, it’s difficult. I’ve written about it directly and indirectly in my poems. Williams’s “Danse Russe” is a wonderful poem on one part of the subject. The connection between art and the soul’s loneliness, or maybe the word—it’s the one he uses–isn’t always right–each soul’s separate task–the part of the self that isn’t absorbed by other people’s needs or answered entirely by love of another–is the reason why there is a need to juggle family life and writing. Anyway, it’s difficult for me. I’ve never figured it out. Partly because it is my nature to be agreeable to others and to set aside what I’m doing, or at least that’s how I choose to see myself, and one problem with it is that one’s selfishness goes underground and is more difficult to pay attention to than the socially admirable parts of one’s character. Complicated: writing comes to be associated with the outlaw parts of the self, but one really needs an orderly, bourgeois life to get work done. Older, I find that the demands of family life are less, but the demands of community life and work life and social life greater, so the problem never really goes away. A work ethic as an artist seems the nearest thing to a solution.

A professor of mine said you are truly a California poet. What do you think this means?

Joel — Miami

Robert Hass: “Truly” is the interesting and puzzling word, Joel. I live in California and write about it. Maybe he means that he sees something in my poems as an accurate (or inaccurately mythic) reflection of California’s culture and geography (but California is a various place).

The Northern Californian landscape figures significantly in your poems; what is its role?

Lacey — New Jersey

Robert Hass: When I was starting to write, I was taken by various regional writers–Faulkner on Mississippi, Dostoevsky as a poet of St. Petersburg, Lowell and New England, and, to a lesser extent, the California poets, Jeffers and Rexroth. I had also begun to be concerned about what was happening to the natural and cultural environment of California in the economic boom of those years. The writing of Gary Snyder and Wendell Berry interested me a lot, then, because they were thinking about how to write about the issues involved, and they were doing it. I liked writing about my place. It gave me a subject; also I have always been very interested in natural history, and I had the idea, in my early work, that the sheer variety of the gene pool needed to be invoked and celebrated, if it was going to be saved, etc. But I found that I wasn’t really interested in or good at advocacy types of writing. It just wasn’t where my subject matter was. So the thought I had went something like this: if I live in my place and live my life and write about my subjects, whatever they turned out to be–love, grief, the nature of things, the nature of our nature, the riddles of existence–and drew on the materials of my place as the idiom of that expression, then that would be the kind of environmental writing I’d do. And that’s roughly how the northern California landscape functions in my work, I think. Though lately I have had thoughts of turning back to it more directly, if I could figure out how.

Are you writing new poems? Where can I read them?

Andrew — New Orleans

Robert Hass: I’ve published only a scattering of recent work, Andrew. Thanks for asking. There was a poem in New American Writing awhile back, the New Yorker recently took a couple of poems. I hope that I am near finishing a book.

How does the landscape and its particular vocabulary help us to understand our relationship to language? I’m thinking about your line, “beard stained purple by the word juice.”

Clare — Baltimore

Robert Hass: In my teaching life, I’ve started trying to figure out how to co-teach, with a scientist friend, an introductory course on language, science, and the environment (I am not even sure, therefore, what word to use–environment, earth, world) and have written a little about this to clarify my own thinking. The short version–because the whole of epistemology is in your question, I think, Clare; Wittgenstein has an answer to your question; Heidegger has a different answer–is that the world given to the senses is the vocabulary with which we express everything that is not visible, or not given to the senses. We can tell people something about thought by describing certain kinds of bird flight, something about certain dispositions of the heart by describing an aspect of trees. This, by the way, makes for a problem with seeing what’s outside on something like its terms rather than ours. Moreover, the “world given to the senses” is drenched in ideas that come from language as soon as it is available to us. Not only stuff belonging to the structure of the particular language we are acquiring as we acquire consciousness, for example (in English the correspondences between, say, the subject-verb-object in the language and cause-and-effect in what goes on out there) shapes what the senses give us, but the pre-linguistic experience of our own bodies–that already informs ideas like “the tree is standing in the field.” “Standing” is already an idea in the mind based on an experience of the body. Perhaps “beard stained purpled by the word juice,” as a thought, falls into this category. I had a dear friend, the philosopher Richard Wollheim. He died recently. A while ago, as I was dithering with these subjects, I said to Richard that I wanted to talk, to go back and think about the little I knew about knowing, because I was teaching this course. He asked how far back. I said, well, how do we know the mailbox is on the corner. And he said, dubiously, I see. Way back.

Could you comment on your poem, “The Seventh Night”? I’ve always assumed it is in a code I don’t know. Is it purely nonsensical? What is the purpose of the playfully outrageous dialogue?

Reynard — Houston

Robert Hass: It isn’t intentionally complicated, Reynard, or written in code, though perhaps the social background is intentionally sketchy, so that the figure of the woman in the poem can be a person or some muse figure conjured by the imagination. I don’t know if it will help, if I say that the social context I had in mind was the last day of something like a week-long gathering of poets (such as occur in the American summer). Hence the seventh day of creation or the beginning of de-creation. So what I imagined was a sort of volleying mix of metaphor competition and flirtatious conversation between two poet or poet-like figures. So when one of them greets the other–I’m not going to look at the poem for the exact lines–“Hello, moonshine,” the other responds back, “Hello, dreamer” and then they start to have a metaphor duel. The woman says who she is by saying, “My father is�” etc.

I love your prose poems in Human Wishes; do you still write prose poems? Can you talk about what prose poems allow you to do that shorter lined and stanzaed poems do not?

Cecilia — Memphis

Robert Hass: I have written some prose poems in the last few years, but I am not really working at the form in the way that I was when I was working on Human Wishes. I think what I said to myself at the time was that the prose form allowed me to get more of the prose of the world into my writing. I think I also was responding against the tendency of the prose poem to be wildly imaginative, free associative, etc, to prove that it was poetry. It had in the late seventies and early eighties devolved into a medium for surrealist skits because it was so afraid of the discursive and narrative uses of prose. So I found myself experimenting with discursive and narrative prose inside the limits of a paragraph.

Will you have a new book soon?

Mike — Kalamazoo

Robert Hass: Soon, I hope. Within a year or so. Thanks for asking.

When Robert Creeley did Poets Q&A, he made the argument that American poetry is too concerned with itself–it doesn’t look outward enough; we aren’t knowledgeable about the countries/cultures with whom we are involved, politically and militarily. Do you agree? Would you say that, despite our blinders, our poems are political nonetheless, in that they don’t take up political issues? Are all poems political?

Ndaneh — New York

Robert Hass: I think each generation of poets and artists has to think out this issue all over again. It is certainly the case that most Americans are deeply ignorant of other cultures. If one lives elsewhere even for a short time and reads other media, gets a different account of the world, then the bubble Americans live in seems, when one gets back inside, absurdly, hopelessly limited and self-pre-occupied. That is true. I picked up a book recently by Dean Acheson, secretary of state in the Truman administration, called The Korean War. In the index, there were, in five or six pages, two Korean names. Our ignorance about Iraq and the Middle East is visiting us just now. Are our poems political by not being political? Yes, sure. But there are also a number of political poems and poems that try to register politics. Are all poems political? That’s something we used to say in the 60’s and it is true, of course, but it’s misleading. Very few of the explicitly political poems in the history of English literature survive into the anthologies we read, and an intelligent Marxist critic could show how the apparently unpolitical poems that do survive have, in fact, a clear political sub-text, but they are for the most part poems of love and sorrow, life and death, social wit, natural description, metaphors for states of the soul. Politics, as a subject, is about government and the effects of government on society. Its particular inventions–laws, written constitutions, monarchial pageantry, prisons, armies, gallows, tax-collection, the separation of powers, equality under the law–are different things, seem to require different skills than invention in poetry. And it isn’t helpful to think they are the same thing. But an appetite for justice, an imagination of peace or fairness or freedom, is an imaginative thing and is poetry’s business, I think. Also, in this country, we have exported so much of the exploitation in which our economic system is implicated that it’s invisible to us. Our wars occur elsewhere, so that the consequences of our politics come to us as displacement, through the media, and it is difficult to figure out how to (1) write about second-hand experience, and (2) get at the politics of our direct experience. Healthy for us, of course, to find ways to do it.

Who are you reading?

Roger — Wisconsin

Robert Hass: At the moment, Rimbaud. I’ve been teaching a course that involves reading Sappho, Catullus, Horace, Li Po, Tu Fu, a little Chaucer, a little Dryden, Baudelaire, Rilke, Vallejo, Montale. I’ve just been reading new poems by my wife Brenda Hillman and my colleague, James Galvin. One of my bedside books has been Happily, by my Berkeley colleague Lyn Hejinian, another is a new book from UC Press, The Seventy Prepositions, by Carol Snow. I have also been looking at the just-published Columbia Book of Modern Korean Poetry.

In an already over entertained world, what do you make of more and more outlets for creativity such as an independent magazine like Smartish Pace? I guess the question is, do we really need another? If so, why? I once heard some poet say, “If you’re thinking of starting a literary magazine, don’t!” Though I must say, it is pretty progressive of Smartish Pace to have poets open to chats on-line.

Russell — Annapolis

Robert Hass: I haven’t seen Smartish Pace. I always like the idea of a new literary magazine. The magazine is clearly going to be reinvented by electronic technologies, but a literary magazine is a kind of literary community–even if, like groups of friends, especially the young in their twenties, they form for a while, generate their excitement and then dissolve. I would think demographics favor more literary magazines. You know, there are more people who can read in most good-sized American cities than there was in Shakespeare’s London or Villon’s Paris. Every city out to produce an interesting literary magazine, and then there are the whole aesthetic movements, people in Seattle in touch with people in Port Royal, Kentucky, and all of them connected with new work all over the world through translation, that can only find their conversation through some form of the literary magazine.

Do you think poetry has withdrawn from the general public? Or, at least withdrawn since the 1950s? At times it seems to have a club feel–a club for members only feel–though I’m wondering who’s to blame (poetry community or society at large) for this feeling. Thanks for taking time to answer my question.

R. Davis — Cincinnati

Robert Hass: I don’t think poetry has withdrawn from the general public. On the contrary, I think–I know, actually–that there is far more public awareness of poetry now than there was in the 1950’s. I don’t know how old you are, R. Davis, or what your gauge of public awareness is. Things certainly change. In my childhood (in the nineteen forties and fifties) there was an older generation still around that had been raised in an educational system that had stressed memorization and public speaking. So, in my experience, my grandparents, both educated in Montana at the turn of the century, could recite at least a few poems–poems that seemed to me sort of fun and sort of corny. And in the local newspaper in the little town where I grew up north of San Francisco there were old-fashioned sounding poems, I remember them all as being about gardening or the seasons, printed in the newspaper. And by the late 1950’s when I was old enough to read the San Francisco newspapers, I remember there was stuff in the paper about beatniks and poetry readings in North Beach, and the trial of Lawrence Ferlinghetti for publishing Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” was a local newspaper story. Poetry was taught in the schools, but no one I knew of read it for pleasure–and the idea of reading poetry in public, which the Beats initiated, was treated as if it were the equivalent of getting naked in public, which they also initiated. There were not ten literary magazines in the entire country; there were–with a couple of noticeable exceptions–no creative writing classes in university, colleges, community colleges, or high schools. The Beats–in my angle of vision in one part of California, began to change that. Robert Frost’s appearance at John Kennedy’s inauguration in 1960 also made for some public awareness of poetry. The elder poets I know or have known–like George Oppen or Stanley Kunitz, who came of age in the nineteen thirties, both spoke about the terrific loneliness and isolation of poets in those years. So it looks to me like the fact of poetry readings in every city, summer poetry workshops regionally all over the country, the dozens of literary magazines, the poetry slams, the fact that there are now one or two poets teaching at almost every institution of higher education in the country, the poetry organizations, prizes, the whole business of poet laureates, the 800-1000 books of poetry published in this country every year–all that looks to me like a more socially active presence of poetry in this country than ever. It is true that it occurs almost exclusively under the radar (the dull Cyclopean eye) of the television set and the local newspaper–but the culture pages of most newspapers simply rewrite the press releases of movie studios and rock concert promoters anyway. So I can see how it might not seem that the culture embraced poetry if one were to judge by the mass media. But there is–I think–an enormous amount of activity all over the country. I am interested by your sense that the poetry world that is out there looks to you like a closed club. I don’t know if this comes from your experience in Cincinnati specifically, or in the country at large. I don’t know how many active poets there are in this country–somewhere around 5,000? There are more stamp collectors, I’m sure, and baseball card collectors. And the published writers do get to know each other and that it looks like a closed club if you are on the outside of it. Probably in that way it is a club–actually a series of little clubs. Poets tend to bond into smallish packs based on their aesthetic commitments and it is often their character, especially the character of avant-gardes and new-poetry movements, to form clubs of those who are against what looks like the main club–which is not necessarily such a bad form for energy to take. I can report that there didn’t seem to be a “poetry community” when I was in my teens and twenties, starting to write, and wondering about making my way. There were the Beat Generation people–who seemed like a group of rebellious like-minded young artists and political activists and adventurous souls, among whom were some poets. And the poets I read in magazines from the East Coast–the quarterlies like the Partisan Review and the Kenyon Review, where I came across poets like Robert Lowell and Randall Jarrell and Elizabeth Bishop–seemed also to belong to a group (to me, from that distance) that included other kinds of writers, novelists and critics. I was getting some of my political education, education in looking at painting and listening to music from the reviews in those magazines, and it felt like the people who wrote for those magazines knew each other, felt, to me, that there was an ideal community out there somewhere of artists and intellectuals more interesting than the world I grew up in, but it didn’t seem like a closed club to me. It felt like an arena of activity. Perhaps the poetry community now is more closed-in on itself, less connected to politics and the other arts, and that may be what you are describing. One solution, of course, is always to create your own club. It is the nature of the arts that each next generation has to turn over the soil.