Jason Gray

by Eric Pankey

Ausable Press

2003

$24/$14

Eric Pankey’s new book, Oracle Figures, opens with an attempt at opening. The speaker of this, and of all these poems, is one looking for a way in, but “The gate cannot open in the overgrown grass.” He continues:

But the way, lit by foxfire and firefly,

By the flint-flash of grit at the pearl’s heart,

Is a past words cannot return to history,

To what the swallows inscribe on the air,

And here, on the outskirts of memory,

I look off again into that distance,

As if into a future, the lightning opening

Before my eyes like Scripture. (“Reconstruction of the Fictive Space”)

It is a book full of symbol and inscription, of mystery and message. The speaker knows there is a possibility that “the equation can be proven” if only he can learn to read the answers given, but he can only see “surface glare, / An afterlife of the afterimage.” The message is lost, and the remnants, shadows of wisdom, are all that is available to him.

Mr. Pankey’s book is that of a journey to find this wisdom (Is there a God? Is there an order?), and he continually looks back to the beginning of creation to find it. But the way is thwarted. He reapproaches the gate of Eden, and even when he can open it because it lies “bitten by salt air and rust . . . unhinged,” the gate leads to “a maze, a riddle of interstices” (“Venetian Afterthought”).

His search is an opened-minded one, trying to scan the entire world for, as the reader is told in “Oracle Figures,” “. . . that moment / In the quarried dark of late winter / When a word begins to adhere to its object.” The voice is looking for that glimpse when a word will finally have its true meaning, and hopes to catch it before it is gone again. To find an answer to the question, he consults many kinds of oracles throughout: auguries of bones, animal tracks, the stars, the I Ching, the path of a spider.

If there is fault to be found in the book, it is that the various symbols and inscriptions which are at times indecipherable to the speaker are indecipherable to the reader as well. The language is wonderful and loaded, but some of the figures can feel impenetrable or, in Mr. Pankey’s own words: “Written down in a calligraphy / so elaborate it was illegible” (“Oracle Figures”). The meaning can get lost amid the ornate figuring. For instance, earlier in the same poem, the reader finds the statement, “Doubt is part of the process of inquiry.” This certainly makes sense, but it is then followed with a series of comparisons: “As is the single star downcast. As is the cricket. / As is the grass. As is the milk on a lynx’s tongue.” Try as I might, I can’t figure out how the milk on a lynx’s tongue is part of the process of inquiry. But possibly all of this is part of the difficult nature of oracle messages. Travelers to Delphi were often befuddled by the mystic’s strange mutterings.

Mr. Pankey has amplified his gift at creating a voice in this book. It is the singular voice calling out that moves these poems and carries us through them. There is stunningly beautiful language here, the rhythm and sound of which are at one with the meaning: “The dragonflies flick the tips of cattails, / Skim the scrim of the stagnant pond” (“Dusk Colloquy with a Ghost”). There are wonderfully observed metaphors: “Each sentence I start to utter begins, / Once. . . / But all I find is a washed-out road” (“Oracle Figures”). The reader can see the speaker’s inability to communicate. All his paths are unnavigable. Even the “utter” is appropriate here with its oracle nature. And there are others: “The wind rattles around in the heart like a janitor with hours still to go on his shift. And nothing left to clean” (“Improvisation”).

Mr. Pankey’s language creates a kind of sonic temple, one that he can pray in and seek out the answer to his search. His quest for God has a compelling corollary question: what has happened to the Garden in our absence? Is it overrun by vines, fountains ruined, or is it waiting for us, perfectly intact, to return?

The speaker’s inability to find an answer to the riddle even leads him to the underworld. Like many journeys before this one, the speaker ends up conversing with various ghosts, including that of his mother. After this sojourn below, the speaker rises back to the surface in “For This World” still looking “back down into the darkness until [his] eyes / Adjusted, until [his] eyes were ready for this world.” Though still unready, the speaker seems at least to acknowledge that he has within himself the capacity to be ready, and that the coming through the darkness will have prepared him for finding an answer. And there is in some poems, “The Coordinates” for instance, a knowledge the speaker has gained, or a plan to obtain that knowledge:

A spider bridges the gap between two oaks.

A black snake slips through a cowlick of tall grass.

I map the coordinates, take rag-tag notes.

Sometimes I can put two and two together.

The collection’s most personal poem, “Night Fishing,” returns to the speaker’s childhood, on a trip with his father and brother:

My father stepped off the path.

Then my brother. I followed.

Even then I was a collector:

A quail feather, a bolus,

Chips of fool’s gold,

Milkweed down, poplar seed.

[. . .]

I collected elements for a divination kit.

A thimbleful of rusted filings.

A horseshoe magnet.

The young boy collecting these fragments of nature for his own “divination kit” is dead-on. It is useful for the reader to see this speaker as human, as a sensitive child, who seems to be at odds with his older brother and his father, but who is trying to figure out what makes them different than him. Later in the poem the speaker continues:

I navigate by the twin tips

Of their cigarettes,

The pulse of burn and dull,

Burn and dull:

The distance between us constant.

There must be a word that means

To knock repeatedly

On a door to gain entrance

And yet not gain entrance.

First my father disappears

Into the canebrake.

Then my brother.

Will the speaker follow, in an echo of the opening stanza of the poem? That is left for us. It seems with what precedes the last stanza, he will not, or if he does, will not find whatever it is that makes them who they are. And this of course has a larger context. In those heartbreaking four lines – knocking and not getting an answer – is the crux of the book. The speaker is trying to find God, heaven, the future, what his soul is and where it is going, but, try and try again, casting die after die, he cannot find any answers. The speaker does not even have the word to express his loss.

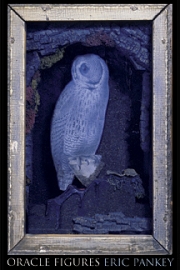

Is God absent in this world? He is silent, at the very least, to the speaker. In “Tableau,” crows give a “cold ministry” and are “angels / In a life without angels.” What he finally settles upon in “Final Thought” is the owl (a figure for wisdom) that “Circles above the lost plan of paradise,” and takes it for his “augur.” The speaker meditates and describes beautifully its “Talon, span, plummet, and swerve, silence subsumed / Into silence, a final thought that tightens / Like a slipknot around nothing and undoes itself.” This seems to be a gesture of understanding that there is nothing there, the message is empty. But it also seems possible that what the undone knot could mean is that God, the creation, cannot be captured in a tangible sign, and that it is continually remaking itself.

Pankey’s final poem, “Leave-Taking Above the Missouri,” lends itself to this. “The way out is up, over, through the thistle gate,” the reader is told. Again the speaker approaches a gate, but this time he goes through. It echoes, at least for this reader, the slogan said in C.S. Lewis’s “Further Up and Further In” as the characters move towards Paradise in The Last Battle — his allegory of Revelations for children. The speaker’s companion quotes Donne to him, “I am re-begot of absence, darkness, death.” Here is creation again. “The world was new: the raw starlight. The river. / The shapes of the shifting sandbar. The third glass of wine, it seemed, a finer vintage than the first.” The speaker has found a contentment in the renewal of things, in the change of things. The wine’s conversion into a finer vintage is immediately recognizable as a nod to Christ’s first mass with his disciples, with a bit of the wedding of Cana mixed in. This is not to suggest that the speaker has become a born-again Christian, but rather that the meaning in these symbols have become new to him, they have been reinvigorated so that the speaker can draw from them a peace, a feeling that there is something on the other side of the gate, and that he will have access to it.

Oracle Figures is a powerful and complex series of poems. It challenges the reader and energizes the language. Eric Pankey’s creation of a voice guides us through the poems, through the journey, even when understanding seems unreachable. It creates its own magnetic field to pull us onward toward the ending, and hopefully back through the gate to paradise.