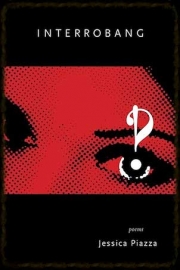

Traci O’Dea

by Jessica Piazza

Red Hen Press

2013

17.95

An interrobang is a little known punctuation mark that depicts a question mark and an exclamation point joined together, sharing the same dot. Jessica Piazza could not have picked a better symbol to encapsulate the effect her book, Interrobang, had on me.

The best books (poetry and otherwise) make the reader smarter. They make us look things up. They make us question (Interro-) things we previously believed, or they make us learn new facts or words (or punctuation marks) we hadn’t known before. Jessica Piazza’s book taught me a boatload of new words—most of which had to do with fears (phobias) and loves (philias). With each read, Interrobang teaches me things because it’s smart. Smarter than I am. But its intelligence doesn’t leave me cold. Because it’s smart without being the tiniest bit pretentious. I mean, Piazza uses italics as well as ALL CAPS IN ITALICS, sentence fragments, wordplay, and sayings like, “Holler back.” That’s where the -bang comes in. The poems look so prettily packaged in sonnet sequences and blank verse and other forms, and many conjure the classics—from Milton to Bishop—with healthy iambic lines. But then her wordplay, slant rhyme, and the shorter lines of the poems “Asymmetriphobia,” “Pharmacophilia,” “Caligynephobia,” and even the tetrameter “Hierophilia,” remind me more of Kay Ryan’s open precision. Here’s the full poem of “Caligynephobia”:

Fear of a beautiful woman

I carry who

I used to be

inside my heart,

a sleight of hurt.The ugly girl

I was at first

lives in this fist,

my hidden trick.Those nights when handsome

boys unstick

and exit, quick,

I wake her upstill in my clutch,

enraged. Then: punch.

It’s in these short-lined poems where Piazza’s terseness alternately broadcasts or whispers her sincere talent as a poet, a poet who says so much in so few syllables—whether the syllables are part of a longer line or not. Maybe it’s because her longer lined poems are so packed with puns and pings and punctuation that I get caught up in the momentum and don’t take time to breathe, such as in the second sonnet in the sequence “People Like Us”:

It isn’t whether. No. Only: how long until

how bad it gets. So quick, our clutch. Sluggish, our rift.

How costly this, a wished subletting of the heart.

Not mine to squat in; he’s not mine (it’s fine). But still:

that sock-to-the-stomach, sudden hollow Ugh! You see

the ante? I’m already un and raveling;

this scanty hope swan-songing my integrity.

(But maybe, also, just a little, reveling?

Piñata pricked, unpilfered? Tamed tsunami swell?

An overflowing loving cup?) Tut, tut! Too cursed.

Too much. I won’t allow it. Silly, sad, or worse:

tonight I’ll disavow these high jinks, hurts, these hells.

(I will? I might.) I must. Such surefire track to lack,

a certain fade to black . . . Oh, fuck it. Holler back.

Upon rereading, I appreciate that the repetition, wordplay, and internal rhyme cause me to make connections and slow down.

Via email, I interviewed Jessica Piazza about the book. No surprise, her replies were full of italics, caps, repetition, and exclamation points. Our emails felt like sisterly, long-distance phone calls with one of us stretching the kitchen wall phone’s yellow cord through the back door to a lawn chair on the porch to watch the fireflies while the other lies on a bed littered with notebooks, novels, dictionaries, and a copy of Strunk & White, twirling a maroon cord around her fingers, both of us geeking out on the topics of wordplay, etymology, punctuation, and what obsession sounds like.

When I asked her about the title, she said she knew she was taking a risk. “I love punctuation generally (so deadly nerdy, I know.) But I also love the interplay between the formal/traditional (which staunch punctuation in poetry represents for me, since there’s so much opportunity to eschew it in favour of the punctuation-free, more experimental poem) and the fun/pop cultural (because the interrobang was a pop cultural product—created by advertisers…and is most aptly used now in the worlds of gossip, of text messaging, of fast-paced and evocative social media conversations.)” People reacted to the title positively, so the risk paid off. “They LOVE LOVE LOVE it because they get the in joke or because they looked it up and were amused, or they are extremely puzzled and a little disconcerted that they had to look up a word to jump into the book.” But we word nerds love learning new words, and most readers are word nerds, so I can’t imagine that too many people were put off by having to look up a new word.

The discussion on the interrobang naturally lead to a chat about punctuation in general. “I’m teaching a poetry workshop right now, and I keep emphasizing to my students that we have this whole shed full or tools (errr, I usually say arsenal full of weapons) we can use to craft (err, force) a poem into being. What a shame to not at least KNOW and have facility with all those tools! What a shame to imagine any tool of poetic craft cannot be a part of our repertoire just because ‘we’re not that kind of poet’! Because all I know is I’m the kind of poet who likes everything having to do with words, and I’ll try anything to get that passion on the page in the best way I can.”

“Your title is also very yin/yang, as is the book—with all these dichotomies of fear and love existing together in one tome,” I next wrote Jessica, “and the fears and loves you write about often get turned on their heads, enforcing the idea of the fluidity of yin and yang. Did your poems ever surprise you by where they ended up?” She replied, “I usually come up with the poem endings first, so I’m rarely surprised with how they turn out, but I’m constantly surprised, however, at how they get there. Writing for me is a never-ending game of word and thought association in my head, generally played backwards from end to beginning. I have a goal, and I have to connect the dots to get there in the most vibrant way I can…When I started the book, I thought of them as the two fundamental, but very different, emotional inevitabilities of humanity. But as I wrote I realized how much overlap they have, in writing and in life. It surprised me at first that often the philia poems were most about fear and the phobias were most about love and lust. Now, though, I’ve internalized that as just another truth.”

Because her poems are chock full of words that derive from Greek and Latin suffixes and prefixes, I asked her how etymology impacts her poetry. “Truthfully, I’m not sure etymology is a big deal for me in poems,” she said, “but diction and wordplay are everything. Okay, sure the historical is an issue in the most contemporary sense—I like to think about how some words are appropriated in our current vernacular. (I’m thinking of slang moments in the book like, ‘holler back,’ which have their own very particular idiomatic meanings that are in direct opposition to their actual meanings.) But generally I’m more interested in how the words play with each other, and with the poem’s meaning, than how they developed historically. Like in ‘Heirophilia: Love of Sacred Things,’ I was excited by the idea of a word triptych, using ‘pray,’ ‘prey,’ and ‘pry’ to work off and against each other to create layered meaning in terms of love and religion.”

We next discussed form, and I asked her about the sounds in her poems: internal rhyme, word play, surprising end rhymes, homophones, homographs, sonnet sequences with reinterpreted end/beginning lines, etc. I also mentioned that in the book, there are several images of imaginary/conflicting sounds: sounds that aren’t there but are there (the conch shell sung into, the tree in the forest). I asked if those images were in any way related to her stance on how form should function in a poem—as a construct that’s there that one can choose to hear or not to hear. Her reply: “Form and music are interesting subjects for me. I’m an obsessive person in general, and REALLY obsessed with obsession itself. These poems are all about obsessions, and it was super important that they sound it.” This is where she described what obsession sounds like. “Well for me, it sounds like pots and pans being banged together. It sounds like the tell-tale heart beating through the floor-boards. Like sirens and sobbing and hyperventilating; it’s relentless and sometimes obnoxious. And frankly, I tried to channel all of that into the music of the poem. The constant internal rhyme, the reiteration of sound and word again and again and again: all those were obsessive gestures for me.” She continued to talk about form. “The form is another thing. These are crazy subjects, and I don’t think most people would go straight to the sonnet (or any traditional form) to explore them. It’s perfect for me, though. A lot of formalists I know write in form because it suits their subjects or personalities. There’s a sense of containment that feels right to people, I guess. But good god, not me. For me, it’s the opposite. I’m chaotic, and I think chaotically, and my instinct is to write chaotically. Training in form was the best thing I could do for my writing to allow that chaos to develop without being too indulgent. I call my style in Interrobang ‘chaos in a box’ because I didn’t want to quell the ruckus, but I did want to make sure it was readable. And, in the end, that’s what philias and phobias are, too. Chaos in a box. They are chaotic, desperate emotions that are boxed in (most often rightfully so) by the constraints of society. So it was fitting.”

Another thing that increases this sense of chaos in Piazza’s book is the fluidity between pronouns representing the speakers and the subjects. The “I” of one poem is not always the same as another nor is the “you” or “she,” yet, by nature, a reader is going to interpret them as connected or possibly as always as the same person, giving the impression of multiple personalities living in the same book.

It sounds like Piazza’s next project, which is not in form, somehow might be less chaotic. “I have a chapbook of ekphrastic poems coming out in a few months from Black Lawrence press called ‘This is not a sky,’ and it isn’t formal at all. I still use rhyme and rhythm as anchoring factors (I probably use them to death, it’s true). But the subject matter this time didn’t seem to want to live in strict forms, so instead I use the conventions and scaffoldings of form to make the pieces sound like I want them to without too much wrestling,” she wrote. Perhaps akin to the shorter-lined poems in Interrobang? I look forward to finding out.

Traci O’Dea lives in the Virgin Islands and has been a member of Smartish Pace since 2003. Highlights of her career as an associate editor include publishing new poems by Medbh McGuckian, procuring new translations by John Hollander, co-founding and judging the Beullah Rose Poetry Prize, organizing the issue release parties, and, of course, co-hosting the AWP event at the TravelLodge Atlanta.