Joshua Mensch

by Gaylord Brewer

Red Hen Press

2011

$19.95

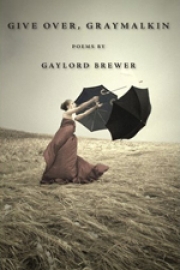

Reading Give Over, Graymalkin, Gaylord Brewer’s eighth collection of poetry, one has the sense of being led into another life. The narrator’s voice feels so familiar, that you might suppose that the book was a memoir in verse – and indeed there’s little to suggest it’s not. Brewer is a deeply personal poet, and in many ways is his own best subject. He speaks frankly and directly to the reader, inviting us into his solitude with a voice that is warm, curious and intelligent.

Organized by geography, the poems in Give Over, Graymalkin, which take the reader from Kenya to India, France and finally to Spain, effectively form a travelogue, and it is to Brewer’s credit that nothing in here reads like vacation poems. Despite the well-worn themes (i.e. a wrecked Western soul seeks solace in the charms of the East only to find the holy steps are crowded with beggars, its wise men are jesters, and no you can’t really run away from yourself), the poems feel authentic, and the landscapes he creates are vivid for their choice, rather than their abundance, of detail. These are places where extreme heat, plus extreme danger, plus extreme poverty, produce extreme humor, and Brewer exploits that early in the book to grab our attention.

The title, taken from a passage from Cormac McCarthy, whose quotation serves as the epigraph to the third section (“Give over, Graymalkin, there are horsemen on the road with horns of fire, with withy roods.”) hangs a particularly apocalyptic shroud over the collection. This sensibility is matched by the opening poem, “After,” which precedes the collection. As a kind of proem, “After” casts a narrative rope around the entire collection. Wearily surveying the landscape he’s left and we’re just about to read, the speaker alludes to the chaos of arrival, its sense of promise, and the hard (and often hilarious) realities that follow in places where people “cage the cold / in winter, heat in summer” and “another / dirty stack” of money is “counted to waiting palms.”

But the real drama is internal. Amidst the chaos, there “rare moments better, / standing privately / under the nights,” where the speaker finds himself “answering / again failures and omissions.”

Finally, coming home, the speaker asks,

“What was a life worth,

beleaguered friend,

when you finally returned,

stinking, unshaven,

parched all the way though?

Dark doorway and key,

hand pushing forward,

one step across to silence.”

The poems of Give Over, Graymalkin are less poems of place than poems of space, in which the narrator inhabits his own psychological state. The mystery at the heart of the book, the emotional core, is the speaker’s past. From beginning to end, one is pulled through the book by an expectation of ultimate discovery, or at least a cathartic release more powerful than any one poem can provide. What complicates the book is Brewer’s deliberate ambiguity about key elements of his plot. The past is alluded to, its events manifested by guilt felt in the present. But by refusing to fill in certain blanks, the poet risks the integrity of individual poems, which draw power from their place in the collection. Put another way, it becomes frustrating to not uncover the source of the speaker’s regret when his regret is central to the plot.

The contradiction, perhaps, is inherent; our guide is a man running away from the very thing he is trying to come to terms with. But other, more concrete ambiguities pervade the narrative as well. One of the central themes concerns the death of a loved one, a recurring source of the poet’s regret. Who, or what, exactly, died, is something that is never made explicit. In poems of such clarity of voice, the ambiguity – even if, puzzle-like, it is resolvable – is frustrating. The poem “Jasper” crystallizes the conflict. The poem starts out with a word that can go either way:

“Dear boy, it was you.

You with me in the house.

I don’t know if I understood

it was a dream or you were

dead. Beautiful, happy…”

The “boy” picks up on the tenor of previous poems about the speaker’s lost loved one, leading the reader to wonder if perhaps a small child had died – and if this were the reason for his wandering. Then adjectival clues are dropped in – “stink-face,” “woofed” – that one associates with a dog. If it seems odd that so much emotional force would be connected to a pet, the end of the poem makes it clear that this pet was like a child to the speaker. The concluding lines, nearly heart-breaking, have the dying animal, who is addressed directly, carried out into the living room, “where your mother / waited just for us.”

The book’s best moments, however, are those in which the poet revels in moments of foreign hilarity. The book’s first section, “In The Gaze of Swami Keerti,” is in many ways an exercise in the ridiculous. Brewer captures well the ridiculousness of going somewhere else – the frequent misunderstandings between a frantic, out of place tourist and his various guides, whose “Every assertion / I was in charge making it clearer I wasn’t”; the frustrations of a well-intentioned foreigner out of his element, struggling, good-naturedly, to adapt:

“I try to conjure an absurd image and come up

with this: me sitting on a floor in India

forcing maniacal stutters, a few select and

hung-over friends watching and shaking heads…”

And of course, the hilarity of imitation as one encounters bizarre reflections of one’s own culture, as in “The Whiskeys of Nainital,” which come with names like Something Special and Soulmate Premium,

“And you, lifting to cracked lips this cool amber,

a double peg ‘long aged, very excellent’

of Old Smugglers – that’s what the label says.”

But danger is always present. In the opening poem of “In The Gaze of Swami Keerti,” the speaker tells us to “Come. Trust me.” But already the next poem introduces a sense of danger. No harm comes, but the fear – the possibility of danger – is visceral. As the poet enters nature, “unarmed,” his “late, heavy lunch” jostling in his stomach, he feels “calm exhilaration.” Only when he presses further, steps into the “head-tall blind of grass,” does he feel “a frission / of panic … // All the easy, / mournful luck of my life, announcing to the wild.”

The speaker is a man who has wandered out of his comfort range, in order, presumably, to better explore himself. Already by the third poem we find the poet in the process of deconstructing the patterns and habits of his normal life. It’s liberating – and enviable.

“Do not, for my own good,

rouse me to clocks

and mirrors.

Please, too, refrain

from custodial

attentions–“

But by the end of the poem, the desire for separation becomes clearer. It’s not just about “turning off” but about cutting off:

“If you care for me, offer only

your absence.”

Who exactly “you” is, is an interesting mystery that deepens the narrative tension. Is the poet speaking to himself? Or to someone else? How does one achieve absence from oneself, and what would drive a man to want that? Of course, being cut off completely is unrealistic, and by the next page the poet is “Calling My Mother From India,” where, in gorgeously concrete detail, he imagines his mother’s “mottled hand” picking up the receiver in a house “Eight thousand miles away / in Kentucky,” already decorated for the holidays, where his father, in the background, “wants fucking sweetener for his cereal.”

The positioning of this poem in the collection is clever. The speaker invites the reader into his childhood home, and in so doing, establishes a sense of intimacy and trust with the reader. We’ve all had that phone call; we can relate instantly to the experience, which is as hilarious in retrospect as it is unnerving at the time.

It’s also a great segue into a funny set of poems centered around Swami Keerti, a spiritual guide who has encouraged the poet to see himself as God. The first of the Swami Keerti poems, “Swami Keerti Reminds Me That I Am God And Suggests Bedtime Meditation” provides a good example of Brewer’s ability to mix the mournful with the hilarious:

“God is going to sleep now….

“He remains unconcerned, however,

by a stubborn chill and a slight fever

by the gaseous result of the soda

He drank for His stomach….”

The poem also serves as a reminder that while nothing is beyond the reach of Brewer’s humor and self-absorption, he is unwilling to merely lampoon or trivialize the subjects of his encounters. For all its dark humor and mournful sadness, this is the source of the book’s greatest strength. Brewer, like Swami Keerti, “is a generous, fine-humored man,”

“appreciative certainly of both attempt

and wretched failure. Don’t be greedy

about godliness, he reminded me,

also that the first taste will be tiny.”

In the end, despite the potential frustrations a less forgiving reader might encounter, the book offers enough gorgeous writing, humor and variety to keep one reading, and probably re-reading, this book.

Joshua Mensch is a Prague-based writer whose poems, reviews and photography have appeared or are forthcoming in Smartish Pace, VLAK, The Poetry Miscellany, Bordercrossing Berlin, GRASP, Rakish Angel, Four Minutes to Midnight, the Prague Post and The Return of Kral Majales: Prague’s International Literary Renaissance, 1990-2010, An Anthology. He has lived in the Czech Republic since 2003.