Karla Huston

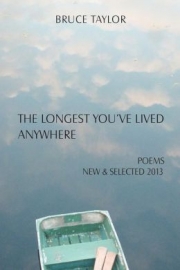

by Bruce Taylor

CreateSpace

2013

$9.99

Plain-spoken without being plain, with language, simple, but not simpleminded, Bruce Taylor writes in a way that allows the reader, allows you in, invites you to sit down and stay awhile. And what you’ll find in a Taylor poem is at once lovely and important, essential and meaningful.

A Taylor poem is a carefully crafted and beautiful thing, his poetic tools, smoothly used with language that is pure and necessary but with a significance that builds to something evocative. From the poem, “The Window:”

Sometimes at night something weeps

inside him, something sits down

with its head in its hands

and smokes and stares.

And in the poem “Everyday” in which the poet examines cold and rainy mornings, the reader finds that this is a love poem about a woman—gone away—but not gone forever.

The fourth morning she’s gone,

the one before the one she

returns again to you.The morning you wait all

the long night for, your one

small light visible for miles.

Taylor, a fixture in Wisconsin poetry for 35 years and author of seven previous collections, presents readers with this compilation “best of” from his book Pity the World (Plain View Press, 2005) and includes new work, which encompasses almost half the book. In poems both new and true, Taylor develops themes which include love and loss, perhaps from the point of view of an older, more experienced man. Taylor’s lover seems sometimes sure of himself, but, more often than not, seems bewildered by it, whether it be dealing with an ex-wife or nurturing a new or existing love. From “What He Does Not Know About Her:”

What songs does she hum in the garden?

What does she wear when she’s sick?

…

What does she say to her husband

when he asks how was her day?

What does she look like walking away?

Another frequent theme in Taylor’s poetry is the inexorable passage of time. His narrator ages but bemoans the process—as we (mostly) all do. He seems resigned and offers readers a view with humor and a bit of self-deprecation.

Taylor “reminds us that life is short/and the world is filling up/with time.” In another poem, he says, “Time passing not so much/as staying and settling, … .” And in another, he says, “He knows the world is round/they said so in school/but he walks it flatly still,/an edge more than horizon.”

There is an irony in Taylor’s aging man. We see ourselves in him and in those moments when he realizes it’s too late to change some things in his life but he might as well live it anyway. “From Calling It the Given:”

The past you thought

would be over by nowa clamor in the heart

a paradise of ruinsits only regret is

it made you what you are

One of the wonders of Taylor’s poetry is his sense of sound and rhythm. He gives readers combinations of the two in sonnets and villanelles that slip so simply into your consciousness, you don’t know you’ve read something in form. He plays with sonics of assonance and alliteration and rhythm together in these lines from “At Mirror Lake.”

Tops of trees shimmer still

following the current of light

rootless in the shallows

where the sky edges the shore.

Notice the alliteration in the words “shimmer” and “still” and the sonic resonance of the short “i” in both words. Notice, too, the dactyls “following” and “rootless in” in lines two and three. The third stanza employs single syllable words, the echoes of the long “o” sound in lone, boat, doze, float, old and dog offer contrast the syllables that surround them.

Two lone boats doze and float

the morning, misty as it settles

the same old man, the same dog,

another day the world allows.

Both sonorous and mournful, these word choices mirror the title. No matter how woeful, Taylor uses a good measure of humor to avoid sentimentality. In fact, the joke seems to be on the poet mostly, his humor like himself—self-deprecating.

“This friggin’ country,” you find yourself saying

lately, or “When I was your age,” betraying

more than you want or used to, and too much

whiskey makes you want to talk too much

which is one good reason you drink it,

you got no time anymore for lawn care or irony

Taylor uses humor and word play in poems like “Travel Advisory” where the poet suggest the reader, “Don’t go.” “Poetry Sex Love Music Booze & Death are discussed in what he calls a “Lite” Sestina. In another, the narrator imagines himself at a writer’s conference with a “slim, bikini’d prose-poet Tai Chi-ing” while others are “jogging up and down/the Robert Frost Trail.”

This book is a delight to read. There are characters, a-plenty, fathers, middle-aged men musing sad and happy songs, and a sense of resignation at the passage of time. Yet, the poems’ themes are human and persuasive. If there is criticism to be made, it is that sometimes the poems seem the same, cover the same ground in the same way. Yet, this is an enjoyable and worthwhile romp with one of Wisconsin’s notable poets.

Karla Huston lives and writes in Wisconsin and is the author of six chapbooks of poetry, most recently, An Inventory of Lost Things: Centennial Press, 2009. Her poems, reviews and interviews have been published widely, including in the 2012 Pushcart Best of the Small Presses anthology. A full collection of her poems, A Theory of Lipstick, is forthcoming from Main Street Rag Publications.