Abigail Licad

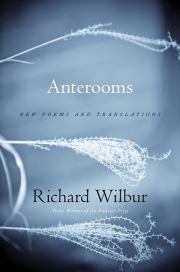

by Richard Wilbur

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

2010

$20.00

Richard Wilbur seems an anomaly in today’s largely postmodern, elliptical, elegiac, multicultural poetical climate. His fidelity to structured form and meter, heavy reliance upon classical antiquity, optimism, and ivy-league background make him something of a throwback to the 1950’s when he first gained public recognition. If his harshest critics are to be warranted in saying that Wilbur did not venture much outside of his formal style and themes, then his new collection Anterooms provides plenty of evidence to lead the way. But why fault Wilbur for refusing the fashionable and sticking with the tried and true, especially when they produce such lovely, musical, and awe-inspiring poems?

Although a very thin volume consisting of less than twenty poems and a few French, Russian, and Latin translations, Anterooms offers powerful evidence of Wilbur’s talents and affirms his place as one of today’s preeminent poets. While the poems here are more benign compared to those from his 1989 Pulitzer Prize-winning New and Collected Poems which were more lush, more urgent, and more ambitious, they continue to display his strong metaphysical bent and his search for the transformative within the bounds of earthly experience.

In many ways, Wilbur abides by his poetical principles, which he frames as his “public quarrel with the aesthetics of Edgar Allan Poe.” Wilbur’s poetry advocates equilibrium, order, control, and rootedness in the natural world over Poe’s surrender to solipsistic, visionary, transcendent imagination. Consider, for instance, how even his war poem “Terza Rima” harnesses violence and chaos into contained form:

In this great form, as Dante proved in Hell,

There is no dreadful thing that can’t be said

In passing. Here, for instance, one could tell

How our jeep skidded sideways toward the dead

Enemy soldier with the staring eyes,

Bumping a little as it struck his head,

And then flew on, as if toward Paradise.

Wilbur deciphered enemy codes as a cryptographer in the Second World War. In the poem, the terza rima’s unity of form contrasts war’s divisions, and the typically Wilburian combination of sonorous cadences, effortless rhyme, and lyrical language mollify war’s miseries. The resulting irony downplays any war trauma while exerting the speaker’s power to keep emotions in check.

Such poetical maneuvers of describing events “in passing” and de-emphasizing painful experiences set Wilbur apart from his earlier confessional contemporaries, Robert Lowell and Sylvia Plath, who tended to outshine him. They were also interpreted by some critics as an evasion of the politics of his day, and perhaps constituted part of the reason he faded into the background when the more politically charged Beat movement came into the poetical fore. However, Wilbur’s physical descriptions – his concentration of war’s ugliness in the soldier’s “staring eyes” and distillation of its violence to “bumping” – however grossly understated, demonstrates his willingness to confront harsh realities, so long as they do not overwhelm the speaker into losing control over himself.

While Wilbur rejects confessional modes, he does take strong interest in the mediating spaces between imagination and reality, the unconscious and the conscious, the irrational and the rational, as embodied in the many types of “anterooms” alluded to by the book’s title. Dreams especially feature in his poems, as do states of becoming, and it is often through these subjects that Wilbur is at his most expectant and optimistic, as shown in “A Measuring Worm”:

This yellow-striped green

Caterpillar, climbing up

The steep window screen,

Constantly (for lack

Of a full set of legs) keeps

Humping up his back.

It’s as if he sent

By a sort of semaphore

Dark omegas meant

To warn of Last Things.

Although he doesn’t know it,

He will soon have wings,

And I too don’t know

Toward what undreamt condition

Inch by inch I go.

The possibilities of transformation pervade Wilbur’s work, as they do in other poems such as “Flying,” “Young Orchard,” Galveston, 1961,” and “Soon.” However, it is important to note that transformation for Wilbur does not mean transcendence, for any changes he explores are always rooted within our physical world. When Wilbur praises or celebrates possibilities, it is often through rich spring imagery. The spiritual for Wilbur exists as palpable experience, not as otherworldly escape. Transformation for him leads to intensified states of feeling and greater appreciation for what exists.

Just as Wilbur’s poems explore states of becoming and transformation, so do his translations enact a kind of linguistic alchemy. Wilbur is not so much concerned with exactness as he is with enlarging meaning. For example, in “An Unpublished Poem” by Paul Verlaine, the only poem in the collection that includes the original French text, a line as simple as “Le monde chante sa romance” (which literally translates to ‘The world sings its love song’) in Wilbur’s hands becomes the more luminous “Mankind intones its lovesick lay.” Such are Wilbur’s deft powers of translation that simple statements become musical phrasings of multi-dimensioned meanings. He takes great liberties, but to beautiful effects.

The poems in the last half of the book display Wilbur’s delightful wit, as they toy with subjects such as a speaking snow shovel, one’s inner egomaniac, and aging. Also included are a group of children’s poems entitled “Some Words Inside of Words” and English translations from the Latin of “Thirty-Seven Riddles from Symphosius.” These rhymes offer a fun break from the interpretive heavy lifting required in the book’s first half, although Wilbur still demands the reader’s imaginative participation and creativity in order to giggle at the word puns and solve the riddles.

In reading Wilbur, one can’t help but marvel at his erudition, his craftsmanship, and most of all, his joyful appreciation for all existence. Here is a poet whose staunch poetical identity has resulted in great contribution to poetry. Reading Wilbur’s poems demands work, but close readers will surely be rewarded. In time, I am certain that critics will rescue him from the ranks of the underappreciated.

Abigail Licad grew up in the Philippines and immigrated to the San Francisco Bay Area at age 13. She received her master’s degree in literature from Oxford University. Her poetry and book reviews have appeared in Calyx, Elevate Difference, and Galatea Resurrects. She is a books editor at Hyphen, an Asian American culture and politics magazine, www.hyphenmagazine.com.