Matthew Campbell Roberts

by William Stafford

Graywolf

2008

26.00

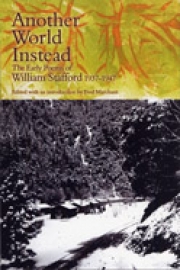

For William Stafford readers, the long awaited release of Another World Instead offers insights into the shaping of one of America’s most prolific poetic voices. From 1937-1947 arrives a collection of Stafford’s virtually unpublished poems that examines, as the title depicts, the author’s tenacious quest for envisioning a new way of life beyond a war he decried. At this volume’s core are impressions of what it was like to be a conscientious objector to World War II. For those familiar with Stafford’s later works, these rare poems are a re-introduction to the young mind of the poet as seeker, wanderer, and reporter. The other gift in this book is the fourteen-page introduction composed with care by editor, Fred Merchant, who conveys a deep understanding of Stafford’s life and work.

After being sentenced to the Civilian Public Service program, Stafford found himself in various work camps including, Los Prietos, California (1942), where he exercised pacifism, and individualism, as a way of venting his disdain for the war by rising at 4:30 a.m.—before the government’s official work day began—to compose poems. Many of these poems are a protest to a world turned blind, a world of absolutism that embraces killing under the guise of liberation. Stafford’s Poem, “Los Prietos [I]” expresses feelings of discontent and banishment: “This is the land we are exiled to from a world fighting. / We look at each other and sing all the songs we have heard.” (28). In these early poems, Stafford’s voice is searching inward trying to understand America’s resentment toward COs who believed in the intrinsic value of life.

Nature is also an escape for the worker/prisoner. Many of the poems in this collection are meditations on the natural world that offers the speaker a way out of the war and work camps. This can be seen in the poem, “Far Down, A River,” as Stafford’s speaker reflects on the river’s struggle drawing parallels to his own:

And I thought of that river: victim of troubles,

leaning its weight to one cliff and another

—all of them losing to time—

and the helpless course of that river

into the vast triumph and quietness of the sea. (37)

Here we glimpse a moment where the speaker, a CO in Los Prietos, California, 1943, shows empathy for the river as a “victim” of its own troubles, both “losing” and “helpless” on its course. But in the end, there is a sense of victory and renewal in bucking the odds as the river dies into the sea.

William Stafford’s poems do not give in to despair; in fact, many poems are meditations that begin with observations of the natural world and hard labor, and then escape into a dream of another place where there is peace—where prison camps for those who do not want to kill no longer exist. This book speaks for those whose lives were disrupted and departed by the hardships of war and its aftermath. It also gives insight into Stafford’s poetic sensibilities and struggles as he developed his practice of daily writing.

From this collection of early poems arrives William Stafford—American poet icon and hero. When reading Another World Instead you can hear the sound of COs’ shovels sifting the earth, the smell of pines in the wind, and hear the rills of streams down in distant canyons offering solace to the prisoner, but also reflecting an eroding world that seems nearly inescapable. Each of these poems measures the depth of the young poet’s heart when faced with adversity. That is what makes this work real, and in an eerie way, seem not so long ago. This book is a must read for anyone who has ever had the pleasure of experiencing a Stafford poem.

Matthew Campbell Roberts was born in Napa Valley, California, where he attended Wooden Valley’s one-room schoolhouse set in the middle of a vineyard. After moving to Washington State he worked a variety of jobs including: deckhand on a purse seine, conservation laborer, stream steward, carpenter, fisheries technician, farm hand, baby’s breath picker, and later became a fly-fishing guide on the Methow River and other waters around the North Cascades. He currently teaches English composition classes at Eastern Washington University where he is also an MFA candidate.