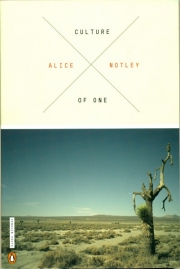

Kascha Semonovitch

by Alice Notley

Penguin

2011

$18.00

Observing thoughts, as a Buddhist might, does not make art, although it might make a better person. The narrator of Alice Notley’s Culture of One has realized this distinction between art and life. She challenges herself concerning the poetic process underway: “Observe your thoughts: are they a poem? No” (94). Abandoning that reflective lyric project, in the next line via the speaker continues another tactic, a narrative one: “A long time ago something happened that I embody” (94). This is the strategy Notley employs throughout. Some poets try to represent thinking itself –consider Hopkins, Oppen or Williams or Carl Philips – and this Romantic attempt has a beautiful history and potential future. But Notely does something else. Lyric poetry has habituated us to expect drama in poetry via a line break, a caesura, or a metaphorical turn within the arc or content of a singular consciousness. Notley, however, contrives drama in its most literal sense: she personifies and diversifies interiority into a narrative stage play.

She tells herself and her reader that it would be worse to “be eaten by / oversubtlety rather than bold red or blue letters howling” (88). That said, this book often subtly navigates the subconscious and conscious tangles of awareness. In other ways, it howls, just as she prefers. Through bold, high-key prosopopoeitic caricatures, the book tells us of MERCY and (Eve) LOVE and MIND who parade across the page as across the stage of a mystery play, demanding to be considered on these direct, archetypical terms. Like Werner Hertzog, Notley doesn’t shy from choosing something over the top to represent something profound, hidden and quite complex. This unabashed provocation invites pity that compels empathy: I suffer for her and then I suffer into her, into myself.

This book is Notely. Or, rather she is it, its monoculuture: “I am / my book: what else would I be?” (30). She is both the living community of characters and its archaeologist searching through its dump, like Marie, one of her arche-characters. Marie, who might also be a real homeless person, seeks a “codex from the dump.” At the same time, Notely’s speaker in the “I” says that she writes this codex: “I will describe what comes to mind. I will draw it and / language it up: it will be mine, an enactment of my culture” (29). The “I” encompasses both narrator who observes as well as the characters in the story. Just as our own consciousness encompasses our thoughts and the witness to our thoughts.

Notley’s culture is “a culture of mercy, / a living codex… a unique culture of one, from everywhere” (35). The speaker reigns as god of this “monoculture” her characters participate in: “The creepy god I am resides in an alcove. Gold crumbles from my / cheeks…. Feel it – This is what a ‘self’ is like // supposedly banished” (19). And what do gods do? They receive sacrifices, or, in rare instances, sacrifice themselves for the good of all. They show mercy. Notley’s speaker, like this rare god, tells herself “I need to be merciful,” and a character named Mercy appears: “Mercy needs no protection, / and has no time for fear. Part of me chooses to be her” (10-11). Notley’s speaker declares herself to also be the character, Mercy: “I told you she is I, though I myself call on her” (34).

What is this “mercy” she desires to be or to offer? Notley alludes frequently to Buddhist associations with mercy and compassion; she addresses “Tara,” the female embodiment or presentation of Buddha, also known as the Mother of Mercy and Compassion. Buddhists see Tara as a divine teacher but also part of one’s own mind. Notley’s characters both teach her and represent her to herself and to the reader. But the “mercy” at work in the text does not only enlighten; it also has a dark side. The book goes to dank, messy places: the dump, a school house full of mean little girls who become Satanists, into covens of witches. If Notely is the God of mercy, then she also kills herself in her mercy. This is mercy as in the French “demander merci” to ask “pardon” or in the New Testament Greek connoting “sacrifice”: a prettier word for killing something to let something else live, instead of a scapegoat who suffers the command of society, the giver of mercy voluntarily gives up herself. Mercy frustrates: “… why does Mercy exist… All she does is use her power, continuously to forgive. Why act then?” (28). Rather than repeat the past, forgiveness allows us to release each other (though not our selves) from the past. But if all actions receive endless forgiveness, endless release, endless new, blank beginnings, why act? We wish the past, we grow into and out of it. Notley says “they try to make mercy less scary than it is by calling it art” (14). She explains that poetry offers a sort of mercy or compassion: “Poetry is la pitié” (39), an embodiment of compassion. And what is it to read if not to suffer into the characters?

Notley takes you on a long, winding, frustrating journey into her mind: it remains uniquely her mind. She uses universal terms – Mercy, Love – but they express her personal configuration and preoccupations. Sharks and witches and dogs populate the book. I don’t know what they mean except the obvious: scary things, friendly things, hidden things. I probably won’t read this book aloud or recite lines of it like I might Yeats or Wordsworth. I probably won’t read this book again. But I don’t read many novels a second time either. This type of writing invites me on a journey and when we reach an end, I feel its singularity. I would find it difficult to flip to a single poem in this project and enjoy it in isolation from the narrative, just as it would be odd to open to the middle of Finnegan’s Wake and truly expect to understand or receive much. You must follow her through the entire drama or not follow her at all. She alludes to hidden motivations and features of her colloquial French landscape that I don’t understand. But I do understand the struggle to represent on the page, the elusive movements of the mind in its diversity and plurality. Observing your thoughts or transcribing them does not a poem make. Creating a cast of characters, a location, a self-referential system of history and allusions – in short, a culture – comes much closer. This is what Notley accomplishes with unparalleled intensity.

Kascha Semonovitch’s poems have appeared in Zyzzyva, The Colorado Review, The Southern Review, The Kenyon Review, The Crab Creek Review and other journals. She holds an MFA in poetry from Warren Wilson College and a doctorate in philosophy from Boston College. While not writing poems, she has taught philosophy, edited books of philosophical essays on twentieth century European thought, and written criticism in art and literature. She edits book reviews for the Kenyon Review Online.