March 7th, 2012

Frank O’Hara and Jan Cremer:

The Amsterdam New York Set or The End of the Far West. 1963 / 1978

Load of Fun

120 W. North Ave.

Baltimore, MD

Fridays: 6 pm—11pm

Saturday: 2pm—11pm

Sundays: 2pm—5pm

Through March 11 (Note: the website says the exhibit runs through February 29, but it has been extended through this weekend.)

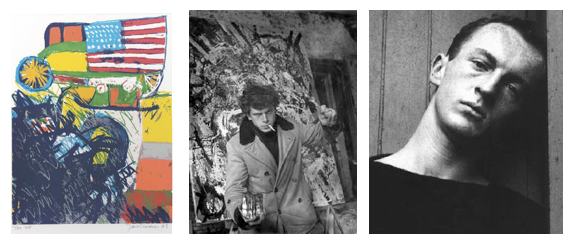

For three decades, Sherwin Mark, master printmaker and the proprietor of Load of Fun, a community-based gallery and venue in Station North, didn’t know anything about Frank O’Hara, despite owning a series of prints—a collaboration between O’Hara and Dutch visual artist, Jan Cremer—since 1978, which at one point he kept rolled up in a zebra pelt. Two or so years ago, he asked Michael Ball, the Baltimore-based poet and founder of the currently discontinued i.e. reading series, if he knew this O’Hara guy. Ball, ecstatic, recognized immediately the importance of the collaboration. With the help of his longtime friend and colleague, Chris Mason, and a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), which wassecured by Ben Stone, director of the Station North Arts and Entertainment, Inc.), this obscure collection found a means to an end with its first U.S. exhibition.

The series is titled, “The Amsterdam New York Set or The End of the Far West,” as opposed to “poems by me drawings by you,” an early suggestion of O’Hara’s. The series consists of ten poems by O’Hara inspired by Cremer’s prints, which clearly show a connection to Pop Art and the combines that blew up the contemporary art scene in the early 60s. Cremer’s vocabulary is limited with the use of wheels, trucks, American flags, and the occasional phallus. But these images were certainly readily recognizable to O’Hara, since his poems riff directly on the visual vocabulary, such as the following taken from the final section of “In New York We Are Having A Lot of Trouble With the World’s Fair”:

The Shakespeare Gardens in

Central Park

glisten with blood, waxen

like apple

blossoms and apples simultaneously. We are happy

here

facing the multiscreens of the IBM Pavilion.

We pay a lot for our entertainment. All right,

roll over.

The poems are blown up and overlarge. O’Hara’s penned corrections remain, as if to remind the viewer of the poems’ spontaneous origin, with only half a thought toward correct capitalizations and typos. But this is vintage O’Hara—dashing off verse, perhaps in a letter to a friend or a moment of lucidity in the whirl of a cocktail party, and then moving on to the next thing. If a cowboy film is on the television, then that’s cause enough for something like “The Green Hornet”:

I couldn’t kill a man when he was drunk

or shoot him

when he’s unarmed, could I?

You sure couldn’t, kid.

Well give me the money.

More of your funny business!

Talk fast, kid. You’ve got just one minute more. Yipe!

Turn that stage team loose.

Do you mind waiting for me

in my office? I’ve got some papers for Judge Hawkins to sign.

You might look pretty.

So Wyatt Earp wrote you a letter?

Told you a lot of things about me?

A girl wants a man

worth sticking to.

Joe Brainard, a longtime friend of O’Hara’s, recounted the writing of the above poem to Brad Gooch, author of the O’Hara biography City Poet:“We were watching a western on T.V. and he got up as tho [sic] to answer the telephone or to get a drink but instead he went over to the typewriter, leaned over it a bit, and typed for four or five minutes standing up.”

In my conversation with Mark, Ball and Mason, we hashed out anecdotes and myths surrounding O’Hara’s life. He was an epicenter, a crossroads of the New York art and poetry scene in the 50s and 60s; and he was ephemeral—here today, gone tomorrow, passionate and fleeting.

“The End of the West” doesn’t feel, ultimately, like a predetermined collaboration so much as it flows like two individuals borrowing freely from common pop cultural vocabularies. There is no guide as to what goes with what; Mark took that liberty himself, and the result is successful in its simplicity. In a brief 1959 essay on poetics, O’Hara summed up, a little pithily, the push and pull of poetry and the poet’s surroundings: “It may be that poetry makes life’s nebulous events tangible to me and restores their detail; or conversely, that poetry brings forth the intangible quality of incidents which are all too concrete and circumstantial. Or each on specific occasions, or both all the time.” That is the essence of O’Hara’s signature “I do this, I do that” poetry, which recreates everyday life and either attaches to its objects profundity, absurdity or neither. In a 2008 New Yorker piece, Dan Chiasson wrote, “That primal cry ‘Here I am!’ is what every O’Hara poem implies—the long, art-starved past now behind him, the beauty of representation having replaced the stultifying air of actual life.” Consider “Chicago” in full:

Death is the Dashiell Hammett idea of idiocy

but Gide agrees with it

it’s red, isn’t it?

and rough and ready?

it’s ready all right

and it isn’t over

not by a long “shot”

but there’s always the alienation of distance

at least from

detonation

“what, may I ask,

was that?”

That was the Walled City and if

anyone sees through my merchant drag

I’ll

go out tomorrow morning

with the garbage

it won’t be an explosion

I’ll be just a package

O’Hara moved easily between pop reference, significant introspection, and whimsy, and his dime-turning verse keeps the readers on their toes.

This series is, in some ways, an anticlimactic end to a long line of brilliant collaborations O’Hara executed with such renowned artists as Franz Kline and Larry Rivers. O’Hara and Kline produced “21 Etchings and Poems” in 1960, a series of diptychs pairing Kline’s abstractions and O’Hara’s poetry (reproduced in his own handwriting). In 1962, O’Hara collaborated with Harold Bluhm and created a lovely series of 26 “poem paintings,” which were collages of images and text.

From 1957 through 1960, O’Hara and Rivers created a series of lithographs titled “Stones.” The two scratched image and text directly onto the stones (backwards since reproductions would appear as mirror images), creating hodge-podge, lyrical narratives.

“The Amsterdam New York Set,” by comparison, is static. While O’Hara and Cremer exhibited a strong chemistry, as well as a platonically romantic bond typical of many of O’Hara’s relationships throughout his life, there simply wasn’t enough time during O’Hara’s dash through Europe to focus on something more in-depth. Sshortly after O’Hara brought Cremer to New York, the poet died in a tragic car accident.

These poems are neither burdened by that knowledge nor are they particularly great examples of the width and breadth of his abilities. But as with so much of his work—work that sat forgotten in typewriters and desk drawers and existed only in letters to friends—his words breathe with immediacy and nerve, all the more so through Mark’s excellent prints.

By Andrew Sargus Klein