Isaac Cates

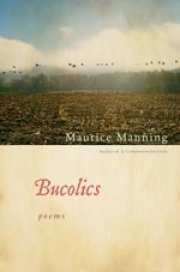

by Maurice Manning

Harcourt

2007

$23

Much madness is divinest sense, or so we are told. Sure, there are a few cliquish strains of methodical madness in contemporary poetry that seem to abnegate all claims on sense. But there are still the very rare outsiders, the visionary books that can astound and surprise even the blasé, well-versed contemporary cognoscenti. Reading more and more, we find less and less of that overwhelming, slightly terrifying thrill that comes from being in the same room as an eccentric genius: Faulkner in As I Lay Dying, Dickinson at her most intense, some of Berryman’s Dream Songs, or James Cummins in his mad sestina sequence The Whole Truth. In the past six years, Maurice Manning has added three books to the short, selective shelf of eccentric American genius, and his latest, Bucolics, is both the most sober and the most significant of the trio.

The pieces in Bucolics don’t have the wild, visionary variety of shapes and voices seen in Lawrence Booth’s Book of Visions (which won the 2001 Yale prize) or A Companion for Owls: Being the Commonplace Book of D. Boone, Long Hunter, Back Woodsman, &c.: there are no poems in the shape of geometric proofs, no petroglyphs or inventories, no rebuses, maps, legal complaints, or diagrams of a man’s foot “Showing Blood, Sundry Wounds, and the Ring of Sadness.” Each of the seventy-eight poems in Bucolics is a brief, unpunctuated monologue in short lines, spoken by an unnamed farm laborer and directed to a figure he conjures by the name of “Boss.” This Boss is the entity or force that most people are taught to call God: the “boss of the blue sky boss / of green water” (XXIX), the “boss of ashes boss of dust” (XLIX), “the biggest boss of all” who “light[s] the candle in the sun” and “dip[s] the water in the rain” (V). The solitary field hand addresses a variety of questions both trivial and grave to this Boss; he wonders, as his seasons progress, about the character of the power or powers that drive both the natural world and his own pleasures and desires. The book thus reveals itself to be a kind of deliberately untutored religious speculation, using a light human touch to insist on one of the most serious human questions: “What is God like?”

Although the fact would be easy to forget, that question absolutely belongs to poetry, because what it asks is an issue of metaphor. The field hand of Bucolics, limited by his landscape to a small set of metaphorical vehicles, nevertheless persists in seeking significant similitudes, though only the intuitive aptness of a comparison can confirm it: his Boss, like any god, remains silent, or speaks in messages that need new metaphors to comprehend them. What can tools and farm implements, for example, teach our man about God? Is the field hand a hoe to his Boss’s hand (“I wonder is that all I am / to you am I that simple Boss / is there a handle in my head / have you fetched me from your giant shed,” LX), or is God in the hayfork (“I’ve made / its handle so shiny from my hands / around its throat so shiny now / it’s like a mirror Boss it’s like / a glass in which I see your face / your burning eye about to wink,” LXIII)? What corresponds to the patch bare of frost melted off of a horse’s shoulder by the field hand’s breath, the “empty eye unblinking” of that darker spot: “which one / of us was that supposed / to be O was it you / so steady Boss or was / that patch of empty me” (XLVII)? Although the images inspiring these meditations are circumscribed by the book’s bucolic setting, the field hand tries every comparison he can, sometimes convinced that Boss is like himself (“do you wipe your face with your shirttail Boss / I’d bet my wages that you do,” IV), and sometimes seeking God in rivers or the sky (“you windy blowhard Boss,” LIV; “you spread the nighttime Boss / all over me,” X). In fact, most of the first half of the book is motivated by a series of questions with metaphors at their base. Many of these seem to be asking to what extent the divine can be understood in human terms:

do you have a table

Boss do you have

a lantern (VII)

how big is your hand Boss hold it up (XV)

if you had a feed sack Boss what

would you keep inside a rooster or

a snake do you need to carry things

around (XIV)

what color is your collar Boss

is your backbone sore from bending over

when you clap your hand against your thigh

does a little cloud of dust fly off (IV)

are you ever sorry Boss ever

have a problem ever get

shamefaced stuff your hands

in your big boss pockets (IX)

If the image of God that emerges through these questions seems unusually limited, it is also unusually humane: a God that not only might “have a nickname,” hold his breath, or “fall asleep,” but might also “notch a stick for every sparrow” (II). Given what our curious plowman knows of himself, he can imagine his Boss motivated by joy, by curiosity, by affection, by spite, or simply by the carefulness of good agricultural husbandry.

It’s tempting to call these speculations revelatory, since each of the field hand’s questions and comparisons feels, at some level, intuitively true (or at least deeply honest): why shouldn’t a laborer’s God also sweat with the work of managing the world? Bucolics certainly has as much to suggest about our relation to the divine as A Companion for Owls has to say about the early conquest of the American frontier. And yet, like the book on Daniel Boone, Bucolics is also a character study and an argument about the psychology of solitary outdoor work, by turns both funny and harrowing. Like Browning’s Caliban, Manning’s field hand reveals a good deal about himself and his life while inventing or contemplating his God; in this way, Bucolics is as much a lonesome blues as it is a philosophical inquiry, because the field hand’s world is populated by himself alone. (It’s tempting, in fact, to imagine him as an Adam without Eve, suffering the curse of labor without having achieved the knowledge of good and evil.) The field hand wonders whether his Boss is capable of the tenderness he feels watching an old dog twitch in its sleep (XI) or the eros of a leaf coming to rest on the surface of water (“all the leaf was trying to do / is cuddle Boss does cuddling move / the likes of you,” XII). Here, for example, the field hand meditates on the question of companionship:

VI

do you get happy Boss do you

get tickled by a funny bird

or doubled over by a tree

a lonesome tree less lonely Boss

because it has a horse beside it

it doesn’t matter if the horse

is rubbing anything or not

as long as it’s beside the tree

so simple Boss a horse beside

a tree it makes me happy just

to think about two things beside

each other the stick beside the fire

the rock beside the water O

the snow beside the sleepy field

O Boss the moss beside my mouth

when I bend down to say it’s me

you mossy bank you happy piece

of green it’s me beside you like

a bird I thought I’d let you know

in case you don’t have eyes I thought

I’d tell you Boss what always leaves

me happy if you didn’t know

already Boss in case you spend

a lot of time beside yourself

As this poem ends, Manning’s unpunctuated sentences create a fruitful ambiguity of address: the plowman stops speaking to the mossy bank and returns to addressing his Boss, but we can’t recognize the “I thought / I’d tell you” as being directed to a new listener until we’re partway into the sentence. This sort of semantic play would be easy to mishandle, I think, but Manning uses his line breaks deftly both to parse his unpunctuated sentences and, as in this case, to create momentarily useful uncertainties. Here, the point indeed seems to be that the prayer (if that’s the right word for the field hand’s speeches) is very much like a greeting whispered into the moss’s ear: a hopeful pledge of fellowship that will not (and cannot) be answered. As it turns out, the solitude of heartfelt religious questioning is at least as great as the solitude of working a farm alone.

This piece is not, indeed, the most heartbreaking plea in the book. That honor belongs either to LIII, in which the field hand imagines himself as a sickened oak tree and asks Boss to “boss back the wind so I / won’t lean so far over . . . / boss the leaves back on my branches / boss the birds back to my arms / Boss them tell them I’m not falling Boss,” or perhaps to XLII, a prayer for the end of a drought. We emerge from Bucolics with a sense that the field hand’s persistently imagined God is his only company—that the laborer needs to imagine his Boss as a companion much more than he needs an explanation for the natural phenomena around him. True, Boss may drive the night like a tired horse across the sky (III) or push the clouds together like a shepherd “stuffing sheep into a chute” (XXXIII), but what the farmer truly yearns to understand is Boss’s relation to himself, in both the metaphorical and interpersonal senses of relationship. “Would you be lonesome if I swam / across the river Boss” (LXXIII), the field hand asks toward the end of the collection; “am I your helper Boss or am / I not” (LXXVII)? Even the seemingly surest assertion of closeness is terrifyingly uncertain. “We’ve always been like this / one finger wrapped around / another Boss that close / but I don’t need to tell / you anything about it,” one late poem begins, but it works its way toward a very different note: “I’m always coming back / around to you O please / believe me do you Boss” (LXXIV). The silence that comes after the ends of these poems is sometimes excruciating.

If Frost is right that “fact is the sweetest dream that labor knows,” then Manning’s field hand, in his search beyond the things of his world, oversteps both his capacity for knowledge and his best hopes for solace. And yet, there could hardly be a more basic impulse than this curiosity about the sower of the stars, the manager of the world. Manning’s genius—his truly staggering genius—is in his ability to put this ancient question into a true American idiom, to make this fundamental human inquiry both vividly, heartbreakingly poignant and madly, idiosyncratically his own. If Manning’s first two books established him as an inventive and eccentric poet of great promise, Bucolics realizes this promise and places him securely among the most important poets of the new century.

Isaac Cates directed the Poetry Center at Long Island University for four years. He now teaches at the University of Vermont. His poems have appeared in Unsplendid, Hayden’s Ferry Review, 32 Poems, and Southern Poetry Review; his criticism has appeared in The Hopkins Review, Indy magazine, Confrontation, and Literary Imagination. Also he has drawn some comics that you can probably find with Google.